FEATURE:

The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame 2026

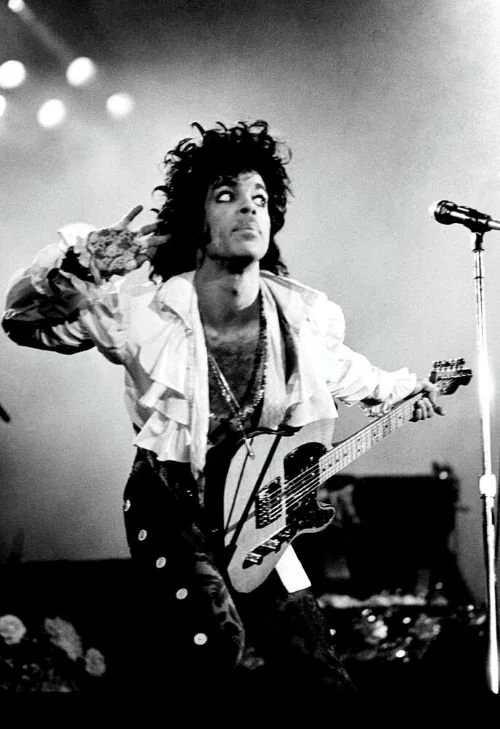

IN THIS PHOTO: Ms. Lauryn Hill

Celebrating the Nominees

__________

IF some are not…

IN THIS PHOTO: Shakira

are not huge fans of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame and what it stands for, I do think that it important and exciting to see artists inducted. Celebrating those who have made a huge contribution to music, an artist is eligible twenty-five years after they release their first record. You can see this year’s nominees here. It is a typically broad and strong list. I would especially love Jeff Buckley and Ms. Lauryn Hill to be among the inductees. The BBC published an article reacting to the nominees:

“Phil Collins, Oasis, Pink and Shakira are among the stars who have been nominated for inclusion in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame this year.

The 17 artists who could be admitted to the prestigious US-based institution also range from Jeff Buckley and Lauryn Hill to Mariah Carey and Wu-Tang Clan.

Artists or bands become eligible 25 years after releasing their first commercial recording.

Oasis and Carey have been nominated twice before, while Pink is now eligible, 26 years after her debut single, and Colombian superstar Shakira could become one of only a handful of musicians from Latin America to have ever been admitted.

Last year, the Miami Herald reported, external that just three out of more than 1,000 individual inductees were born in Latin America.

The Wu-Tang Clan are the only hip-hop act to be nominated

Wu-Tang Clan's nomination comes after Gene Simmons from veteran rock band Kiss recently criticised the inclusion of hip-hop artists, saying they don't "belong", external in the Hall of Fame.

First-time nominees:

Jeff Buckley

Phil Collins

Melissa Etheridge

Lauryn Hill

INXS

New Edition

Pink

Shakira

Luther Vandross

Wu-Tang Clan

Returning nominees:

The Black Crowes

Mariah Carey

Billy Idol

Iron Maiden

Joy Division/New Order

Oasis

Sade

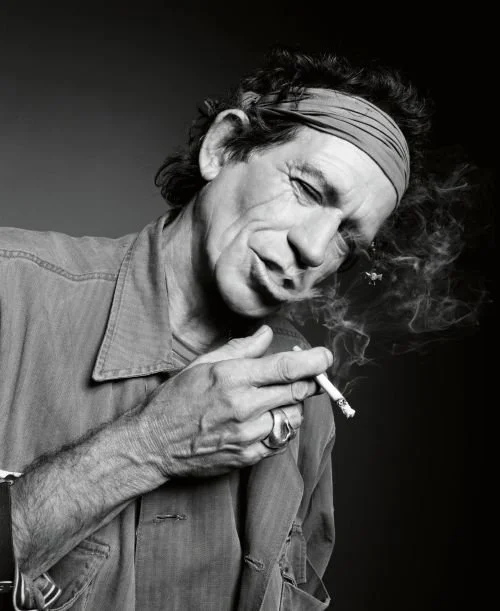

Collins, 75, entered as a member of Genesis in 2010, and has now been shortlisted for his solo work including 1980s hits In the Air Tonight, Against All Odds (Take A Look At Me Now) and Easy Lover.

He would be a popular choice after his music has been discovered by a new generation, and after he has suffered a series of health problems in recent years.

Phil Collins performed seated on his last tour, and recently revealed he has a 24-hour live-in nurse

He recently told Zoe Ball on BBC Radio 2 podcast Eras that "everything that could go wrong with me did go wrong", adding: "I have a 24-hour live-in nurse to make sure I take my medication as I should do."

He explained: "I got Covid in hospital, my kidneys started to back up, everything that could all seemed to sort of converge at the same time. And I had five operations on my knee."

Collins, the father of Emily in Paris star Lily, also said he would "love" to tour again but wasn't sure he wanted to "go as far as to launch that boat".

His last major solo tour was the Not Dead Yet Tour from 2017 to 2019, and he performed seated during the Genesis reunion world tour in 2021 and 2022.

He also told Ball he may go back into the recording studio to work on "some things that are half-formed or were never finished".

Meanwhile, Oasis will discover whether their successful reunion over the past year has enhanced their reputation as legends in the US, a country they famously struggled to fully break first time around.

But singer Liam Gallagher has repeatedly criticised the Hall of Fame, previously saying he wasn't interested in receiving an award from "some geriatric in a cowboy hat".

He added, perhaps sarcastically, that Oasis didn't deserve their nomination "as much as Mariah [Carey]".

"She smashed it," he noted.

Mariah Carey has been nominated for the past three years - could it be third time lucky?

Carey, meanwhile, has previously noted that "my lawyer got into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame before me," referencing entertainment lawyer Allen Grubman - who also represented clients like Madonna, Bruce Springsteen and Lady Gaga.

There's strong British representation on this year's list - Billy Idol, Iron Maiden, Joy Division/New Order and Sade are all up for induction at the second or third attempts.

Sade last toured and released an album 15 years ago

A panel of voters normally chooses between six and eight performers to be inducted from the nominations.

The selected acts will be revealed in April, and the star-studded induction ceremony will take place in Cleveland, Ohio, in the autumn”.

To celebrate the incredible artists who have been nominated for induction and inclusion into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, I have compiled a playlist of their work. Two songs from each artist. There is going to be a lot of interest around those who are selected for induction in April. I think that it is an amazing rundown of artists who are all very worthy. Here is a mixtape celebrating the remarkable…

ROCK & Roll Hall of Fame nominees.