FEATURE:

‘YES’

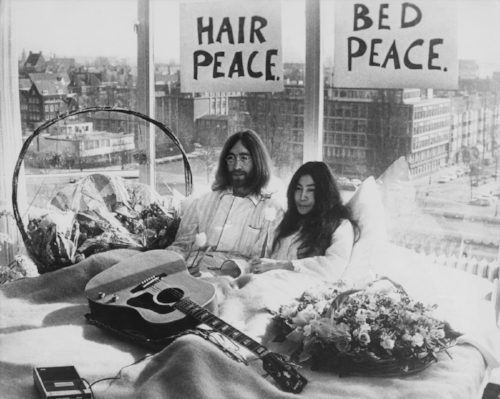

IN THIS PHOTO: John Lennon and Yoko Ono during their ‘bed-in’ at the Presidential Suite of the Hilton Hotel, Amsterdam in 1969/PHOTO CREDIT: Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

John and Yoko’s Early Bloom (1969-1971): A Spirit the World Would Do Good to Take to Heart Today

__________

I was among many who sat down and watched…

the John and Yoko documentary, Above Us Only Sky. The title comes from a line in John Lennon’s famous song, Imagine (which was co-written with Yoko Ono). One of the best revelations from the documentary was how John and Yoko met. The exact date of their meeting is unknown but, as Lennon said in the documentary; he was looking at an exhibit of Yoko’s in the Indica Gallery, London, and saw this tiny ceiling painting. Scaling the ladder placed underneath it, he was curious to see what was written on the painting – the word ‘YES’ was what he saw. He was gripped by the oddity of the scene but the affirmative message compelled him to meet the artist (it would have been around 1966). The fact someone would paint something with a positive word and get people to climb a ladder to look at it, in many ways, set the course for their relationship and how John and Yoko would write. Last night’s documentary seems to have hit a major chord with critics. The Telegraph provided their thoughts:

“This wasn’t so much the untold story of the making of a classic album as a fascinating addendum to an iconic story which had already been told in the companion film released by Lennon, Yoko Ono and director Steve Gebhardt in 1972, and fleshed out even more in Andrew Solt’s tribute Gimme Some Truth...

Here director Michael Epstein took the story further. He had access to Lennon and Ono’s personal archive and, for obsessives, unearthed previously unseen film footage of recording sessions, interview material, and early run-throughs of Imagine, Jealous Guy and How? But what this film really did was provide context. Not only in the words and memories of people who contributed musically to the album – drummers Jim Keltner and Alan White, bassist Klaus Voormann among others – but also friends, hangers-on, assistants, photographers and journalists who captured a precise moment in the personal and creative lives of Lennon and Ono.

More than anything, though, this film sought to give Ono the equal credit many (including Lennon in a 1980 interview replayed here) said she should have had for her contribution to Imagine’s title track. As a result, what emerged from what might otherwise have been just a gentle retrospective was a remarkably rounded picture of two emotionally fused and radically engaged talents working together to condense their thoughts on art, politics, love and music into one of the best-known and commercially successful protest songs ever.

In so doing, it also reminded us of how and why Lennon’s – and Ono’s – central message of peace, love and people-power remains so potent to this day”.

It was a compelling story that used footage from various stages of their relationship. A lot of the feature concentrated on the album, Imagine, in 1971 but there were interviews with Lennon and Ono and contemporary viewpoints from people who worked with the couple. One of the biggest realisations from the documentary is how potent and meaningful that message of peace is today; how John Lennon and Yoko Ono wanted people to come together and how much we need to take that to heart today.

PHOTO CREDIT: Iain Macmillan © Yoko Ono

I was moved by the intimacy between Lennon and Ono and how naturally the former Beatle put these masterful songs together. It was wonderful looking in the studio and that mix of casual and serious. Players (such as George Harrison) and producers were milling and smoking; shooting ideas around by there was always that professional atmosphere. Lennon’s serious tone and commitment to the work was essential – to ensure the very best work was coming forward. There are myths and exaggerations regarding Yoko Ono’s role in breaking up The Beatles. Many assume her close bond with Lennon divided the band and meant his focus was away from the band and he was more committed to her. Yoko Ono, throughout her relationship with John Lennon, was subjected to racist abuse and misconceptions. After The Beatles’ split I 1970, it was only natural the two would start making music together. To be fair; their start was a little ropey. The conceptual trio of albums they put out in the late-1960s was not well-received by critics. Unfinished Music No. 1: Two Virgins featured that famous cover of the two naked – the results, as critics noted, was a disaster. The second edition, Life with the Lions, featured actual silence and all sorts of weirdness and conceptual guff. It was slayed by critics and the third piece, Wedding Album, was simply two tracks/sides – John & Yoko and Amsterdam – that tested even the most ardent John Lennon fan. It was a rather sorry end to the decade for Lennon and one suspects the guidance and influence of Yoko Ono defined the tone and concept of these albums!

The 1970s, the first part of the decade, was when the work of John and Yoko really shone. Their peace-loving attitude and humanity was affecting the work more but, as much as anything, after an unstable and testing time for John Lennon; Yoko Ono was having this stabilising and positive impact. 1970’s John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band was an album of self-recovery and reflection. Lennon and Ono, before the album, undertook primal therapy and it was a way for both to channel and expunge childhood traumas – as opposed more conventional therapy methods. Although there was a lot of peace and togetherness in the album; there was the odd shot against his old band, The Beatles. God features a dig – “I don’t believe in Beatles” – and Paul McCartney would be the subject of future songs. Reviews for John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band were extremely positive. AllMusic provided their thoughts:

“It was a revolutionary record -- never before had a record been so explicitly introspective, and very few records made absolutely no concession to the audience's expectations, daring the listeners to meet all the artist's demands. Which isn't to say that the record is unlistenable. Lennon's songs range from tough rock & rollers to piano-based ballads and spare folk songs, and his melodies remain strong and memorable, which actually intensifies the pain and rage of the songs. Not much about Plastic Ono Band is hidden. Lennon presents everything on the surface, and the song titles -- "Mother," "I Found Out," "Working Class Hero," "Isolation," "God," "My Mummy's Dead" -- illustrate what each song is about, and chart his loss of faith in his parents, country, friends, fans, and idols. It's an unflinching document of bare-bones despair and pain, but for all its nihilism, it is ultimately life-affirming; it is unique not only in Lennon's catalog, but in all of popular music. Few albums are ever as harrowing, difficult, and rewarding as John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band”.

Mother, one of Lennon’s most beautiful tracks, addressed both of his parents. He was abandoned as a child and his mother, Julia, was hit and killed in a car accident in 1958. It is an emotional and revealing song that showed a different light to the icon. A lot of the later Beatles songs by Lennon were cynical and not at his usual standard. The first three albums by Yoko Ono were weak and this was the first time John Lennon was able to break away from The Beatles and create something masterful. Working Class Hero is Lennon’s most revolutionary and political song; a look at how working-class people are processed into the machine and overlooked. Isolation is about the disillusion and detachment Lennon felt after The Beatles split; how he turned to drugs and the reaction he and Yoko Ono were receiving. God, one of the album’s most striking songs, looks at false idols and people he doesn’t believe in – including Hitler and Jesus – and how, if there is a God, then we are all in it/him. The impact and legacy of the album, as told here, is undeniable:

“The results put a period on everything that came before, even as they made clear the safety he found in his relationship with Ono. The act of walking away from the Beatles' dizzying celebrity on "God" may have gotten the headlines, but Lennon ends up naming and then discarding all of his earlier talismans – only to follow with a quiet affirmation of his affection for Ono. As with so much of this cathartic, utterly remarkable project, even that came from a deeply honest place...

Still, Plastic Ono Band remains Lennon's most consistent, and most important, solo work. Every part of his convoluted genius – Utopian dreamer, angry brawler, lonesome orphan, naked provocateur – is found here, and it's laid bare inside the most stripped-down, revelatory setting of his solo career”.

IMAGE CREDIT: Getty Images

This first bloom of John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s partnership was transforming this troubled and isolated songwriter and transforming him back to his very best self. Although the real heart of the Lennon/Ono peace explosion would take place later; the brilliance and chemistry that defined John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band was defining Lennon’s next phase. The introspective and open tone of the record, I feel, has Yoko Ono all over it and allowed Lennon to move (John and Yoko were accompanied by The Flux Fiddlers) onto Imagine and start this revolution; a chance of peace and a genuine movement that caught the world’s attention. 1971’s Imagine was a more elaborate and ambitious effort than the previous year’s work and, with new confidence, the songs were among John Lennon’s very best work. The album was written during a bad period where there was tension between John Lennon and Paul McCartney. How Do You Sleep? Is a rather harsh and direct attack against McCartney following his jab against Lennon on the album, Ram. Lennon explained, in subsequent interviews, how the two were still hanging out and it was more creative rivalry than hatred.

Imagine’s title anthem is Lennon’s defining moment and seems to be the distillation and definition of the love he and Yoko Ono shared. Although writing credit has been changed to include Ono – it used to be credited solely to John Lennon – her fingerprints are in there and you can sense this man yearning for equality, unity and harmony throughout the world. The song, alongside the bed-in and protests that followed- pricked governmental ears and Lennon was seen as someone who could lead a hippe revolution against the then-U.S. President Richard Nixon. One reason why last night’s Channel 4 documentary got to me was because of the genuine desire to change things and spread the message of peace. Imagine did feature songs with bitterness and plenty of anger but it was tracks like Imagine and Jealous Guy that showed this tender, inspiring side. Jealous Guy started life of Child of Nature – on The Beatles’ 1968 eponymous album – and is one of the most revealing and stunning songs in Lennon’s cannon. Many cannot connect with a song like Imagine because they feel it is hypocritical. Lennon, as a millionaire, was talking about having no possessions and there being no God. The thing with attacking Lennon on those grounds is the overriding message is one of peace and harmony.

He would have given everything away to see that happen and millions of pounds does not buy peace or give you power. Lennon’s personal wealth has nothing to do with what he was trying to deliver: a paen to a new world and a change in the wind. I see the period of 1969-1971 as being especially memorable and inspiring. One might say the musical height of John Lennon and Yoko Ono, on their two titanic records, did not do much to halt the Vietnam War and bring about unity. What they did in 1969, as this article explains, was revolutionary:

“It was the year 1969, 14 years into the deep morass of the Vietnam War. Richard Nixon had been in the White House for two months, and San Francisco’s “Summer of Love” was all but a fading memory as American troops continued to drop bombs on Vietnam and Cambodia. But despite all this, a fervent push for peace and utopianism was percolating over 5,000 miles away—in a hotel room in Amsterdam.

In late March of that year, the press received word that Beatles star John Lennon was “holding court about something or other” in Room 902 at Amsterdam’s Hilton Hotel, overlooking a wide canal, as a reporter remembered years later. Lennon and his partner Yoko Ono, an artist associated with the Fluxus movement known for making art out of everyday life, had married in secret five days earlier in Gibraltar. Now they were planning to use the inevitable press frenzy that would follow to spread the message of love, “like butter,” as Lennon would later put it to reporters...

From March 25th through 31st in Amsterdam—and then from May 26th to June 2nd at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel in Montreal, Canada—Lennon and Ono received visitors between the hours of 9 a.m. and 9 p.m. They coddled babies, sung with rabbis and Hare Krishnas, played with Ono’s daughter Kyoko, argued down conservative media figures, and dispensed advice on how to resist the establishment, urging onlookers to get their hands dirty for the cause. Sometimes their advice came straight from Beatles song titles and lyrics: “Come together” or “All you need is love!”

They expounded on the importance of unity and the shared bonds of humanity, and broadcast a .it’s an achievement to brush your teeth,” Lennon would say during the couple’s second “Bed-In.”

At the time, the “Bed-Ins” attracted mixed reviews. “Beatle Lennon and his charmer Yoko have now established themselves as the outstanding nutcases of the world,” ran one headline, Kruse notes, while Rolling Stone was considerably more supportive: “A five-hour talk between John Lennon and Richard Nixon would be more significant than any Geneva Summit Conference between the U.S.A. and Russia.”

Years later, Ono would reflect back on her role as one part of Mr. and Mrs. Peace, as Lennon referred to them. “John and I thought after ‘Bed-In,’ ‘The war is going to end,’” she recalled. “How naive we were, you know? But the thing is, things take time. I think it’s going to happen. I mean, that I think we’re going to have a peaceful world. But it’s just taking a little bit more time than we thought then”.

There were some scrappy moments, musically and politically, by John Lennon and Yoko Ono between 1969 and 1971 but they were sensing something needed to change and trying to bring about peace. Aside from the Imagine album and the bed-in; it was a huge part of Lennon career where he transitioning from the break-up on The Beatles and creating some of his very best work. The biggest impression and takeaway from the Lennon/Ono golden years is the message of peace and that need to come together. Lennon’s voice is needed more than ever and we need this musical guidance. Alongside the incredible music and passion between Yoko Ono and John Lennon was this dream of stability in the world. We are so far from what they were preaching in the late-1960s and early-1970s and, at a time when there was the war in Vietnam and a corrupt U.S. government; people wanted things to be better and the violence to end. A lot of parallels remain and I wonder what John Lennon would make of today’s world. The quality and striking nature of the music he was making back then was a reaction to wars. There was this global carnage and division but there was a personal one, too. He was adapting to life outside of a band and undergoing therapy so that he could try and come to terms with harrowing memories and demons. Few expected much musical genius after the ill-conceived and ridiculous trio of albums between John Lennon and Yoko Ono but they managed to combine their powers and create two remarkable albums in John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band and Imagine. It was a wonderful and hopeful time and one we need...

SO desperately today.