FEATURE:

Once in a Lifetime

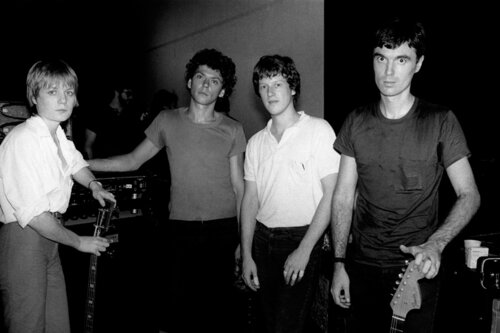

Talking Heads’ Remain in Light at Forty

___________

SOME big album anniversaries…

have already happened this year, but today (8th October) is the fortieth anniversary of Talking Heads’ Remain in Light. It is the fourth studio album from the band, and it was produced by Talking Heads’ long-term collaborator, Brian Eno. Led by the incredible David Byrne, Remain in Light was the first Talking Heads album I came across. I think it was the single, Once in a Lifetime, that hooked me into the band, and I was instantly struck by that song! I think there was a feeling, on previous albums and 1979’s Fear of Music, that the band was a front for David Byrne, whereas Remain in Light was a shift and a more inclusive album; one where the band experimented with Nigerian music and looping grooves. Although David Byrne suffered some writer’s block during Remain in Light’s creation, he adopted a stream-of-consciousness approach to lyrics and was inspired by academic literature on Africa. I do not think I had heard too many African elements in music prior to discovering Remain in Light. I guess Paul Simon’s Graceland (1986) was an album where the sound of Africa was present, but there were not too many albums from my childhood where we had that blend of accessible and conventional sounds with something more unusual. I think the reason why I loved Remain in Light from the start is that it was so original and different from anything around, in the sense that there are so many sounds merged together and we hear these brilliant songs flow effortlessly!

There is plenty of complexity and genius, but the album can be appreciated by all. As a child, I was powerless to resist Talking Heads, and I listen to their music a lot still. Although David Byrne has gone solo and the band’s last album, Naked, was released in 1988, I think they are inspiring artists today and we can look back at albums like Remain in Light as classics. Even though Remain in Light weas released in 1980, I think it is one of the best albums of the decade, and I think it helped bring African rhythms and music more to the forefront. The album peaked at number-nineteen on the U.S. Billboard 200 and number twenty-one on the U.K. Albums Chart. I think the greatest strength of Remain in Light is the variety of sounds and how diverse the album is. With some Art Pop and Dance Rock mixed with that African influence, it sounded like nothing else at the time – and it is still in a league of its own. Remain in Light is an album that sounds great on vinyl - and this is how Rough Trade describe it:

“The musical transition that seemed to have just begun with Fear of Music came to fruition on Talking Heads' fourth album, Remain in Light. "I Zimbra" and "Life During Wartime" from the earlier album served as the blueprints for a disc on which the group explored African polyrhythms on a series of driving groove tracks, over which David Byrne chanted and sang his typically disconnected lyrics. Remain in Light had more words than any previous Heads record, but they counted for less than ever in the sweep of the music. The album's single, "Once in a Lifetime," flopped upon release, but over the years it became an audience favourite due to a striking video, its inclusion in the band's 1984 concert film Stop Making Sense, and its second single release (in the live version) because of its use in the 1986 movie Down and Out in Beverly Hills, when it became a minor chart entry.

Byrne sounded typically uncomfortable in the verses ("And you may find yourself in a beautiful house, with a beautiful wife/And you may ask yourself, well, how did I get here?"), which were undercut by the reassuring chorus ("Letting the days go by"). Even without a single, Remain in Light was a hit, indicating that Talking Heads were connecting with an audience ready to follow their musical evolution, and the album was so inventive and influential, it was no wonder. As it turned out, however, it marked the end of one aspect of the group's development and was their last new music for three years”.

I will wrap up soon, but I want to bring in a couple of reviews. Remain in Light received widespread acclaim on its release in 1980, and it continued to accrue praise and accolades years after its release. In their review of 2012, here is what the BBC had to say:

“Remain in Light wasn’t the first time Talking Heads, helmed by the inimitable David Byrne, had worked with producer Brian Eno. Nor was it the first time they’d incorporated elements of "world" music: debut set Talking Heads: 77’s opener, Uh-oh, Love Comes to Town, features steelpan sounds from the Caribbean. But it was (is!) the indubitable zenith of both the band’s Eno collaborations and their explorations beyond art/post-punk and new wave templates.

Whilst Byrne and bandmates’ intentions from the outset were framed by the desire to experiment, Remain in Light is a perfectly accessible affair, never losing sight of the following Talking Heads had attracted via minor single hits like Psycho Killer and their cover of Al Green’s Take Me to the River.

This mainstream-savvy sensibility is encapsulated by Once in a Lifetime. Far from Remain in Light’s most riveting moment, it’s nevertheless the ideal introduction to this set: Eno’s introduction of Fela Kuti-inspired rhythms lends the track a savant edge, but Byrne’s aspiration-meets-realism lyricism connects with a universal audience. With MTV offering support come the station’s 1981 launch, the track was Talking Heads’ best-known song until it was out-radio-played by 1985’s Road to Nowhere

Road to Nowhere’s parent LP, Little Creatures, can’t match Remain in Light’s bravado, though. This fourth album illustrates how keen ambition could gel with commercial nous, with results that dazzle. Even in its darker turns - closer The Overload the obvious example -these eight tracks continue to fascinate over 30 years after their creation.

In short: same as it ever was, same as it ever was…”

There is no doubt that Remain in Light marked a real turning point and peak for Talking Heads. I think David Byrne’s lyrics especially come to the fore, and he produced his best work with the band on the album. At forty, Remain in Light still has the power to startle and intrigue the senses. I want to source from a Pitchfork review of 2018, where they talk about the album’s strengths and why the album is so important:

“The musical transition that seemed to have just begun with Fear of Music came to fruition on Talking Heads' fourth album, Remain in Light. "I Zimbra" and "Life During Wartime" from the earlier album served as the blueprints for a disc on which the group explored African polyrhythms on a series of driving groove tracks, over which David Byrne chanted and sang his typically disconnected lyrics. Remain in Light had more words than any previous Heads record, but they counted for less than ever in the sweep of the music. The album's single, "Once in a Lifetime," flopped upon release, but over the years it became an audience favorite due to a striking video, its inclusion in the band's 1984 concert film Stop Making Sense, and its second single release (in the live version) because of its use in the 1986 movie Down and Out in Beverly Hills, when it became a minor chart entry.

Byrne sounded typically uncomfortable in the verses ("And you may find yourself in a beautiful house, with a beautiful wife/And you may ask yourself, well, how did I get here?"), which were undercut by the reassuring chorus ("Letting the days go by"). Even without a single, Remain in Light was a hit, indicating that Talking Heads were connecting with an audience ready to follow their musical evolution, and the album was so inventive and influential, it was no wonder. As it turned out, however, it marked the end of one aspect of the group's development and was their last new music for three years.

Although Remain in Light has become an acknowledged classic, it retains a feeling of unfamiliarity. It is tempting to attribute this quality to Byrne’s obtuse lyrics, but the album’s instrumental arrangements also constitute a break with rock’s conventional forms. Weymouth’s bassline on “Crosseyed and Painless” crowds staccato bursts of notes into the first half of each measure, leaving the second half empty in a way that defines the percussion pattern. This technique, essential to funk, diverges from rock’s standard practice of using the bass to keep time. Perhaps the album’s greatest heresy, though, is its total absence of guitar riffs. Like Weymouth, Harrison prefers to use his instrument as a noisemaker. His howling fills on “Listening Wind” lend a foreboding, unpredictable atmosphere to lyrics that are as close as Byrne gets to conventional narrative. These tracks do not hew as strictly to Afrobeat forms as “Once in a Lifetime” or “Born Under Punches (The Heat Goes On),” but they still manage to introduce a coherent sound that is alien to mainstream rock”.

Remain in Light’s legacy is huge. It was named one of the best albums of 1980 by many publications at the time, and, in 1989, Rolling Stone named Remain in Light as the fourth-best album of the decade. In 1993, it was included at number-eleven in NME's list of The 50 Greatest Albums of the '80s. Many other newspapers, music magazines and sites have listed Remain in Light among the best albums of all-time. I know that Remain in Light will receive a lot of love today, and many will nod to a very important album. I got hooked on it as a child, and I have loved it ever since. Albums as extraordinary as Remain in Light come about….

ONCE in a lifetime.