FEATURE:

Moving

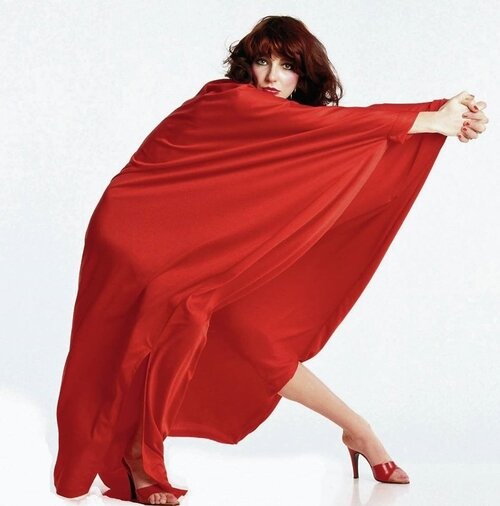

IN THIS PHOTO: Kate Bush in 1993/PHOTO CREDIT: Guido Harari

Kate Bush and Dance

___________

I am sort of sticking in the early years…

IN THIS PHOTO: Kate Bush in 1979/PHOTO CREDIT: Gered Mankowitz

when it comes to Kate Bush. My last feature concerned Lionheart and how it is vastly underrated – Bush’s second studio album was released in 1978. I have discussed Bush’s music from a variety of angles, but I have not really focused on love and use of dance. I guess I did mention it when discussing her Tour of Life and how physicality and movement really defines her best videos but, in so many ways, it is Bush’s attachment and dedicated to dancing that, in my view, really brought her music to life. Whilst dance did not feature as much in Kate Bush’s videos from, say, Aerial (2005) to the present day, I think that was not an abandonment of dance; if you listen to the albums, most of the songs are less physical than her earlier work. Before Bush recorded her debut album – but after EMI has spotted her talent and was preparing this promising star -, there was something missing from her lie. I cannot imagine that Bush’s school life provided many opportunities for interpretative dance. Bush did take Dance classes at school, but the teaching was very formal, and the relationship between Bush and her Dance teacher was not strong. Sure, Bush excelled in English classes and had her poetry published in the school magazine; she took violin lessons and had a definitely passion for music but, until she fell under the spell of Lindsay Kemp, there was this definitely hole.

As we can see on this page from the Kate Bush Encyclopaedia, it was difficult to get into dance when she left school:

“Once I'd left school I tried to get into a dance school full-time, but no one would accept me as I had no qualifications in ballet. I had almost given up the idea of using dance as an extension of my music, until I met Lindsay Kemp, and that really did change so many of my ideas. He was the first person to actually give me some lessons in movement. I realized there was so much potential with using movement in songs, and I wanted to get a basic technique in order to be able to express myself fully. Lindsay has his own style - it's more like mime - and although he studied in many ballet schools and is technically qualified as a dancer, his classes and style are much more to do with letting go what's inside and expressing that. It doesn't matter if you haven't perfect technique. (Electronics & Music Maker, 1982)”.

Graeme Thomson’s excellent biography of Kate Bush, Under the Ivy: The Life & Music of Kate Bush, spends some time looking at Bush’s early relationship with dancing. Lindsay Kemp’s Flowers – a re-imagining of Jean Genet’s Notre Dame Des Fleures – was a seismic moment for Kate Bush. Bush saw the production in Bloomsbury and Chalk Farm, and she was mesmerised by the power and originality of Flowers.

The fact that it was such an unusual and moving piece of theatre would have been transformative for someone whose exposure to dance prior to this experience – Bush saw Flowers in 1975 – was relatively traditional. Bush would learn and spend hours doing dance routines at her family home at Wickham Farm, where songs such as The Beatles’ Eleanor Rigby would be honed and explored. Bush was inspired by Gurdjieff’s Fourth Way – the notion that mind and body are not separate creative entities, and the secret to fulfilment and realisation is being able to fuse the two -, and she referenced this important lesson in The Kick Inside’s Them Heavy People (as I mentioned in a feature earlier this year, where I discussed Bush’s love of literature and cinema). I can picture a young and hungry Bush paying 50p a session to take mime lessons with Lindsay Kemp – each session would last about three hours. I think these early experiences were pivotal when it came to Bush’s music and how she would incorporate movement and dance into her music; how she would bring the emotion from her songs and represent them in this very bold and inventive manner through her videos. I will not repeat what I said in my literature/cinema feature, but dance and mime allowed Bush the chance to free various voices and personas within herself; to dive into various characters and, in the process, become a stronger and braver individual. Bush then started taking classes in Dance at the Dance Centre in Covent Garden, where there were these drop-in classes five days a week – she did this for over a year.

IN THIS PHOTO: Kate Bush in 1978/PHOTO CREDIT: Gered Mankowitz

When the late Lindsay Kemp talked about him teaching Kate Bush, he explained how she was very reserved and timid to begin – hiding at the back of class -, but was encouraged to the front and, very soon, blossomed and stood out from the rest. Bush’s dancing was not great to start with but, as she was lured by the unconventional, she, fuelled by discipline and determination, grew and improved – Bush was very tough on herself, and she was eager to succeed. One of Kate Bush’s tutors, Robin Kovac, was instantly struck by Bush, and she helped the songwriter with the famous and much-imitated routine for Wuthering Heights. From as early as her debut single, Wuthering Heights, in January 1978, dance was a central part of Bush’s psyche. Many of her contemporaries were creating simple dance routines for their music videos, but very few were pushing boundaries and had this very intimate and evocative relationship with movement. My first exposure to Kate Bush was watching the video for Wuthering Heights when I was a child. The song was definitely special, but it was Bush’s routine and incredible aura that struck me hard. This article from AnOther magazine outlines how Buh’s music videos were game-changing:

“From the very beginning, Kate Bush’s career has been defined by her pioneering synthesis of music and movement. Signed to EMI at just 16, she spent two years honing her craft by enrolling in dance and mime lessons with Bowie collaborator Lindsay Kemp before releasing any music at all; on her first (and only) tour she instructed her sound technicians to develop the first ever microphone headset so she could dance and sing simultaneously, changing the possibilities of live concert performance forever.

With the sensual shiver and outstretched arms of Wuthering Heights and the elegant, expressive pas de deux of Running up that Hill, Bush’s music videos also introduced a wider public to contemporary dance. In the case of the latter video, the choreography was considered so radical that MTV were unwilling to screen it and chose to air a live performance of the song instead.

It’s also a remarkable testament to the power of dance to explore our most primordial frustrations: sex, death, desire, and most movingly here, Bush’s grief. Only two years before, her mother Hannah had passed away suddenly, and along with the recent death of her guitarist and a romantic break-up with a close collaborator, she used both album and film as a means of processing these losses — most movingly in the sequence that accompanies Lily, as Bush rests her head in the lap of a kindly looking old woman.

When discussing the Running up that Hill video, Bush noted that she saw other musicians using movement “quite trivially… haphazard images, busy, without really the serious expression, and wonderful expression, that dance can give”, countering this by dressing herself and fellow dancer Michael Harvieu in simple grey Japanese hakamas, the camera quietly following them around a spartan room lit only by moonlight”.

So many people lionise Kate Bush because of her incredible lyrics and that staggering voice but, to me, I think it is dance that really defines her – and is the reason why her music and music videos have an essence and nuance that makes them indelible and captivating. When Kate Bush started out – and her debut album arrived -, a lot of the promotional photos revolved around her a dancer.

I do not think she was overly-sexualised in those photos, but I do love the photos Bush shot with Gered Mankowitz (where she was dressed in a leotard) as, like her music, there was this fluidity and physicality that seduced and stuck in the mind. I do feel there is this very direct and entrancing correlation between dance and Bush’s music; how she almost dances her way through songs and gives her words flight. Maybe I am not explaining it well, but it is obvious than early experiences with Lindsay Kemp and dance classes deeply influenced Bush’s songwriting and music videos. There were periods where Bush sort of put dancing on the back burner – especially around the time of The Dreaming in 1982 -, but she reignited that passion for Hounds of Love. On each album, you get a new experience and style in terms of dance. Look at the video for Sat in Your Lap from The Dreaming, and it is more frenetic; Running Up That Hill (A Deal with God), and The Big Sky from Hounds of Love is different to what we would see on The Sensual World (from the album of the same name), and Rubberband Girl from The Red Shoes. Whilst Bush’s 1993 film, The Cross, The Line and The Curve, was largely panned by critics, it is notable for (among other things) Bush’s routines and her marriage of movement and music.

The article from AnOther magazine that I quoted from discussed how Bush could create simple routines and blow you away because, in everything she did, that love of dance was evident:

“So too in The Cross the most powerful sequence is the most simple: Bush pirouetting slowly as if flying through outer space, singing album highlight Moments of Pleasure directly to camera with a sheet of silk billowing behind her. While her lyrics are known for their esoteric references, here the song itself is an uncharacteristically straightforward exploration of heartache and bereavement: “Just being alive / It can really hurt / And these moments given / Are a gift from time”. Whirling gently, she begins to smile, as if the sheer joy of moving her body is giving her the impetus to carry on. Despite its flaws, Bush’s belief in the therapeutic power of dance gives the film a memorable resonance, and it’s worth watching merely as a rare insight into the interior life of a fiercely private icon”.

IN THIS PHOTO: Lindsay Kemp and Kate Bush in 1993’s The Line, the Cross and the Curve/PHOTO CREDIT: Guido Harari

From The Kick Inside’s opening track, Moving – dedicated to mentor Lindsay Kemp, who “crushed the lily in my soul” (in other words: he brought the fire and physicality out of a timid young woman) – to her video for King of the Mountain (where Bush evoked the spirit of Elvis Presley), the symbiotic and crucial bond between dance and music has defined Kate Bush and elevated her above everyone else. I would recommend people watch her music videos, as it is impossible to look away and not fall under her spell! I have not even mentioned her two live extravaganza: 1979’s Tour of Life, and 2014’s Before the Dawn residence (I have covered both in various features), which allowed Kate Bush the chance to give her songs almost theatrical and cinematic levels of movement and reality. It was clear from The Kick Inside’s Moving that, that early, dance was life-changing for Bush – “You give me life, please don't let me go (please don't let me go)”. Bush might not have known it, but her study and dedication to dance and mime (in 1975/1976) would not only open up something inside her, but it would…

CHANGE the music world forever.