FEATURE:

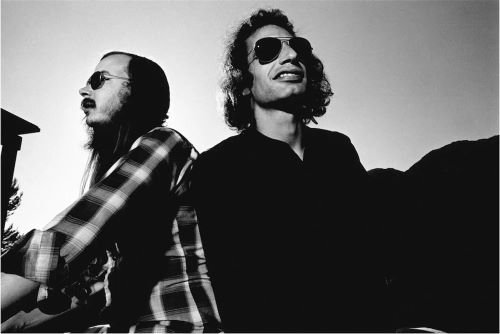

I Got the News

Steely Dan’s Aja at Forty-Five

__________

THE sixth studio album…

from Steely Dan, Aja turns forty-five on 23rd September. Recording alongside almost forty musicians, band leaders and songwriters Donald Fagen and Walter Becker pushed Steely Dan’s sound further into experimentation. More so on any other album, they played with a different combinations of session players while pursuing longer, more sophisticated compositions for the album. Reaching three in the U.S. and five in the U.K., Aja is the best-known and reviewed album of their career. With stunning cuts like Peg, Deacon Blues, and Josie, this is a classic album. Aja won the Grammy Award for Best Engineered Recording – Non-Classical in 1978. I will try and do it justice but, as one of the most immaculately produced album ever heads towards its forty-fifth anniversary, I want to bring in a couple of articles that look at the story and making of a genius L.P. I am going to end with a part of a review from Pitchfork. The first feature I want to start with SPIN’s essay and examination of Aja back in 2017:

“These people are too fancy, they’re too sophisticated,” William S. Burroughs said of Steely Dan in 1977. “They’re doing too many things at once in a song.” Burroughs, who had no personal connection to the band, had been asked to comment on Aja, Steely Dan’s new record, because co-founder Walter Becker and Donald Fagen had named themselves after “Steely Dan III from Yokohama,” the surreal dildo featured in Burroughs’ most notorious novel Naked Lunch. His comment embodied a common-man criticism made about Steely Dan by their detractors: The unit, who stated their claim in the pop sphere with clean, blues-steeped singles like 1972’s “Reelin’ in the Years” and “Do It Again,” had gradually but consistently ceased to resemble a meat-and-potatoes rock band, instead spiraling off into groovier, jazz-inspired pop experimentalism.

The effect heightened as Fagen and Becker systematically fired all of their band’s other members, and replaced them with industry-standard jazz, soul, and blues musicians. They stopped touring; the songs’ narratives and jokes became more acidic and obscure. Rolling Stone’s review of 1976’s sprawling, sinister The Royal Scam summarized the feelings of the band’s skeptics and newfound admirers alike, that they would “eventually produce the Finnegan’s Wake of rock.” On the day Aja came out, Walter Becker told Cameron Crowe that he was empathetic toward the concerns, but also uninterested in compromise: “These days most pop critics, you know, are mainly interested in the amount of energy that is…obvious on the record. People who are mainly Rolling Stones fans and people who like punk rock, stuff like that… a lot of them aren’t interested at all in what we have to do.”

Instead of the Rolling Stones or punk rock, Aja was deliberately intellectualist pop music that appealed easily to music-school types and jazz fans–chops-y rock music that helped “legitimize” the genre. Becker and Fagen’s songs, charted out across six or seven sheets normally, prized and necessitated technical musicianship. They used horns as expressive, exalted instruments in rock songs, not just padding or blunt, skronking deus ex machinas. But the record’s appeal extended well beyond the ranks of any subgenre of snobs. Standard-issue rock listeners, after all, indulged in elaborate, preciously-conceived, and strange things in the 1970s, a decade which yielded four Top 10 albums for Emerson, Lake, and Palmer.

40 years later, Aja is still Steely Dan’s commercial triumph. It was their only record to sell over a million copies, spawned three Top 40 singles—”Peg” hit No. 11—and stayed on the charts for well over a year, peaking at No. 3. In 1977, the music industry was at the apex of LP sales and mammoth recording budgets. In the year-and-a-half Fagen and Becker spent making Aja, the Dan would push their studio expenses into the hundreds of thousands, all while not playing live. On its 20th anniversary, Becker would chalk Aja’s success over past Steely Dan ventures up to the right-place-right-time factor: “That was a particular time when people were just selling lots of records.” They assumed, he said, that “‘we’re gonna sell three times as many records as we would have two years before.’”

Much gets made of how obsessively Fagen and Becker would plot parts for musicians, but many of Aja’s best and most famous were defined by their players’ independent innovations. As bass player Chuck Rainey recalled in the Steely Dan biography Reelin’ in the Years, Fagen and Becker had specifically told him not to slap his bass during the sessions for “Peg.” Rainey responded by turning his back to the control room and slapping away. Fagen and Becker liked the sound, despite their prejudices, and Rainey went on to slap again on “Josie.”

Then there was Bernard Purdie, one of soul music’s most inimitable drum stylists, who told the story of taking control of the direction of the recording of “Home at Last” himself in the Classic Albums episode on Aja. “They already told me that they didn’t want a shuffle. They didn’t want the Motown, they didn’t want the Chicago,” Purdie explained. “But they weren’t sure how and what they wanted, but they did want halftime. And I said ‘Fine, let me do the Purdie Shuffle.’” It was precisely what Fagen and Becker hadn’t asked for, until they heard it. Purdie would go on to use the same beat on one of the Dan’s greatest singles, Gaucho’s “Babylon Sisters.”

Meanwhile, drum prodigy Steve Gadd foiled the duo’s plans for the day by running down the intricate title track of Aja in just one take. For the most muso-focused listener, his epic, virtuosic solo in the instrumental middle of the song is the beating heart of the album, layered over with chunky horn charts from arranger Tom Scott and alien synthesizer atmosphere (an anomaly for a Becker/Fagen recording at the time.)

Like their hero Duke Ellington, Fagen and Becker needed the identity of individual soloists to create their finished canvas, but within quite specific and refined structural limits. The duo was not as good with people as Ellington, but they didn’t have to be. From the safety of the studio booth, they could just say “try it again” as much as they needed, and scrap the solos they didn’t like after the fact. According to Reelin’ in the Years, the band’s career-long producer Gary Katz would break the disappointment to the players by talking to them about baseball, before dropping the news that their solo—which the person had spent hours trying to hammer out—would not make the record. When it came to the prospect planning a live tour behind Aja, they got as far as rehearsals, but ultimately backed down.

“We had 4,000 dollars worth of musicians in the room, guys who wouldn’t go out on the road for Miles Davis, literally, and they were committed to doing this,” Fagen explained. “And we both left the room together and said, ‘What do you say, you wanna can it?’ And we both said ‘Yeah’ without thinking twice.”

The ambition of the music and their (Crowe’s words) “heinous” studio antics were not the sole, or perhaps even the main reason, for Steely Dan’s lasting reputation as curmudgeons. The narrators of their songs were creeps. On early Dan albums, Fagen and Becker spun autobiographical yarns about intellectually overzealous young men who were bitter beyond their years, both sending up and romanticizing their youthful steady diet of Beat literature, low-grade weed, and worn-out Sonny Rollins LPs. On Aja, those bad and sad men were grown up into shadowy, morose personalities, their faces averted like the lonely guy at the counter in Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks. The album solidified Steely Dan’s obsession with what Fagen would call a “culture of losers” in earnest, with Deacon as the self-appointed superhero of the bunch”.

One of the very best albums of the 1970s, Aja has this perfect musicianship and songwriting. At forty minutes and seven songs, it has this focus to it - and yet many of the songs are allowed to breathe and unfurl. It is a stunning record. Classic Album Sundays provided a wonderful story about Aja. I first hard the album when I was a child. It was a part of the family vinyl collection. I still never tire of its brilliance and impact! I get something different from Aja every time I approach it:

“As Michael Phalen famously comments in the liner notes of Steely Dan’s sixth studio album, “Aja signals the onset of a new maturity and a kind of solid professionalism that is the hallmark of an artist that has arrived.”

Phalen, of course, was simply another illusion crafted by the ironic and somewhat bitter imaginations of Walter Becker and Donald Fagen, the two masterminds behind the enigmatic “non-band” who were gaining a reputation as some of the most difficult yet brilliant musicians of the 1970s. In late 1977 the pair had revealed Aja, an album which would come to define their legacy as a stubborn yet accomplished musical powerhouse, as they staked their territory in an increasingly fragmented and contradictory musical landscape. The album was a sumptuous and expansive collection of music; one that has rightly earned it’s reverence as an audiophile masterpiece.

Steely Dan had gotten off to a promising start with their debut album, 1972’s Can’t Buy A Thrill, from which the two hit singles “Do it Again” and “Reelin’ In The Years” Billboard charted at number six and eleven respectively. Guest vocalist David Palmer was often drafted into live performances to compensate for Fagen’s persistent stage fright, but the latter’s voice was clearly preferred by his band-mates, leading to Palmer’s exit during their first tour. This initial boom was followed by a notable downturn, as the group’s second album Countdown To Ecstasy, released a year later, failed to breakthrough commercially, with Becker and Fagen blaming a hectic touring schedule for its rushed and under-baked content.

Bouncing back with their most successful single “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number”, which peaked at Number 4 on the Billboard chart, Becker and Fagen found renewed energy in their eagerness to recruit new and exciting session players. Their 1974 album Pretzel Logic followed a period of touring with keyboard player/vocalist Michael McDonald, vocalist/percussionist Royce Jones and session drummer Jeff Porcaro (who would eventually go on to form Toto with Katy Lied Pianist David Paich.) Porcaro proved a reliable and consistent collaborator over the years, but joined the group as a creative fissure between Becker/Fagen and the rest of the band was widening. Echoing Brian Wilson of The Beach Boys, the pair were disillusioned by the obligations and restrictions of live performance, gravitating towards the creative reclusiveness enabled by the recording studio and it’s increasingly powerful tools. As the band’s creative directors they became harder and harder to please, often demanding that musicians perform around forty takes of the same recording.

Guitarist Jeff Baxter and drummer Jim Hodder, who remained particularly keen to tour, and felt insulted by their increasing redundancy for session players, eventually left the group along with the other core band-members, excluding Denny Dias who remained a member until 1980. Left to their own devices the pair revelled in their ability to assemble a rotating cast of musicians, each of whom they could draft in for minor or major contributions as they saw fit. As such, they began to decentralise the notion of Steely Dan as a solid group of musicians into something amorphous and indefinable, thus commencing the period of uninhibited creativity that birthed Aja.

Having cultivated a reputation as stubborn yet masterful songwriters, the pair now possessed a certain magnetism which allowed them to assemble a dream-team of jazz, r&b and rock virtuosos, who could actualise their sonic fantasies. Included on this list was legendary saxophonist and Miles Davis alumni Wayne Shorter (who rips through a solo on the album’s title track), drummer Bernard Perdie (responsible for the groove of “Home At Last”) and Steve Gadd, amongst many others. Far from assured by the proven talents of these musicians however, Becker and Fagen took their hairsplitting scrutiny to new and extreme levels, famously sifting through dozens of separate recordings of the same guitar solo for “Peg”, before landing on Jay Graydon’s pitch-perfect performance.

Considering the somewhat pressurised atmosphere surrounding these sessions, it’s easy to see how this ethos carried over into the album’s pristine sound quality. A truly lush and all encompassing audio experience, each instrument boasts a rich glossy veneer, penetrating and tessellating with an almost surgical precision. Far from clinical however, this exceptional clarity maintains the minuscule, if calculated, nuances of each musicians contribution, and ultimately serves as testament to their tight and disciplined performances.

Released in 1977, the year that both the lighting force of punk and the carefree abandon of disco were enjoying cultural hegemony, Aja found itself strangely out of time and place; an irregular jigsaw piece in an often polemic commercial environment. It was around this time that predominantly white rock fans where denouncing the perceived superficiality of repetitive black dance music. But Steely Dan had also been the subject of their ire. As Michael Duffy’s review in The Rolling Stone noted: “Aja will continue to fuel the argument by rock purists that Steely Dan’s music is soulless, and by its calculated nature antithetical to what rock should be.” Far from immune to this criticism, Becker and Fagen reportedly remixed the album around 13 times in the months prior to its release”.

I am going to conclude with a review for the supreme and magnificent Aja. Pitchfork gave the album a full ten when they provided their take in 2019. I think that this is an album that people will be unpicking and dissecting for decades to come. Masterful songwriting by Walter Becker and Donald Fagen, combined with superb production by Gary Katz (with Becker and Fagen) and some peerless playing from the band, this is an album that should be preserved for all of time:

“Steely Dan is generally associated with Los Angeles, where they made most of their records, but Becker and Fagen are both New Yorkers (Becker was born in Queens; Fagen was born in suburban Passaic, New Jersey), and their sensibilities were plainly shaped by a kind of wry, East Coast cynicism. It manifests most palpably in Aja’s lyrics, which are funny, surreal, and, for the most part, narratively ambiguous. On a song like “Deacon Blues,” which they co-wrote, it’s impossible to deny the precision of their phrasing, and the unexpected depth of the song’s sentiment:

Learn to work the saxophone

I play just what I feel

Drink Scotch whiskey all night long

And die behind the wheel

They got a name for the winners in the world

I want a name when I lose

They call Alabama the Crimson Tide

Call me Deacon Blues

Becker later said the song was about the “mythic loserdom” of being a professional musician—how glorious it might look from the outside, how grueling it is in practice. “Deacon Blues” is a fantasy of art-making, spun by someone who has never had to do the work, and therefore requires a funny sort of narrative distance: Becker and Fagen were looking at their own lives from the perspective of someone who wants what they’ve got, but also someone who fundamentally misunderstands the costs.

Aja produced three excellent singles (“Peg,” “Josie,” and “Deacon Blues”) and sold millions of copies, becoming the group’s most commercially successful release. But it was a perplexing bestseller. Steely Dan spent the 1970s getting progressively more esoteric: jazzier, groovier, weirder. Even now, mapping the album’s melodic and harmonic shifts is impossible to do with confidence. Its songs are sprawling and fussy, populated by oddball characters with inscrutable backstories, like “Josie,” from the song of the same name (“She’s the raw flame, the live wire/She prays like a Roman with her eyes on fire”) or “Peg,” an aspiring actress headed who-knows-where, who’s “done up in blueprint blue.” “Blueprint blue”! It’s the kind of simple, perfect description prose writers pinch themselves over.

Outside of the studio, Becker and Fagen reveled in being a little rascally. They took long breaks from touring, and when they conceded to an interview, they often appeared self-satisfied, if not antagonistic. Their disdain for the record business occasionally bled into a disdain for their fans, itself a kind of merciless, punk-rock pose. When they did tour—like, say, in 1993, when, after a decade-long hiatus, they booked a few weeks of U.S. dates—they did not pretend to enjoy it. That year, when a reporter from The Los Angeles Times asked Becker how the tour was going, he said, “Well, not too good. It turns out that show business isn’t really in my blood anyway, and I’m looking forward to getting back to working on my car.”

Because the production on Aja is so expert—whole stretches are perfect, impenetrable, like the first 31 seconds of “Black Cow,” when that creeping bass line cedes passage to guitar and electric piano, and the backing vocals pipe up for “You were high!”—it’s easy to ignore the sophistication of its architecture. Becker and Fagen used obscure chords (like the mu major, a major triad with an added 2 or 9) and custom-built their own equipment (for 1980’s Gaucho, they paid $150,000 to build a bespoke drum machine). What they were doing was so particular and new, it was often difficult for critics to even find a vocabulary to describe it. On the title track, the verse shifts and dissolves as Fagen croons, “I run to you.” His voice thins as he finishes the line, a little gasp of tenderness. The minute-long drum solo that closes “Aja,” performed by the virtuosic session man Steve Gadd, is dressed with horns and synthesizers, and makes a person briefly feel as if they are being transported to a different dimension. Steely Dan reveled in making technical choices that would have hobbled a less ambitious outfit. That they succeeded still feels like some kind of black magic.

By 1977, it is possible that some corners of the culture had become desperate for music that was intellectually challenging but not exactly arduous to consume—something less predictable than Top 40, but not quite as hyperbolic or gnashing as punk. By the end of the 1960s, rock had been relentlessly and breathlessly defined as a frantic, bloody, all-consuming practice, for both performers and fans. Aja, though, doesn’t necessarily require any sort of deep emotional entanglement or vulnerability from its listeners. In that way, the record works as an unexpected balm, a break—a little bit of pleasure just for pleasure’s sake”.

On 23rd September, Aja is forty-five. Considered one of the greatest albums of all-time, it has been discussed by music journalists as an important release in the development of the Yacht Rock genre. As only the odd song from Aja is played on the radio – I guess Peg and Josie more often than the other tracks -, I am not sure whether young listeners are discovering it and how widely known Aja is among that demographic. In 2010, the Library of Congress selected the album for preservation in the National Recording Registry for being "culturally, historically, or artistically significant”. You only need to hear Aja once to…

UNDERSTAND why.