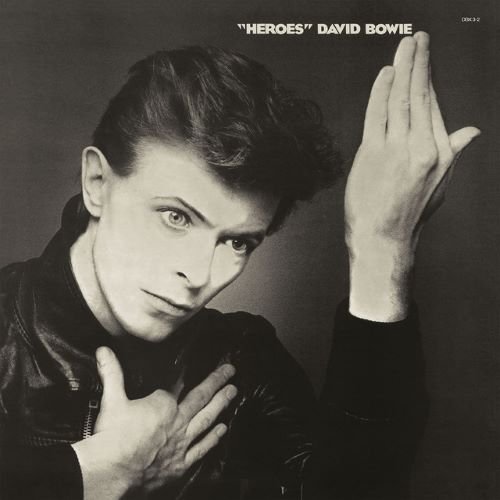

FEATURE:

Just for One Day…

David Bowie’s “Heroes” at Forty-Five

__________

WHEREAS the title song…

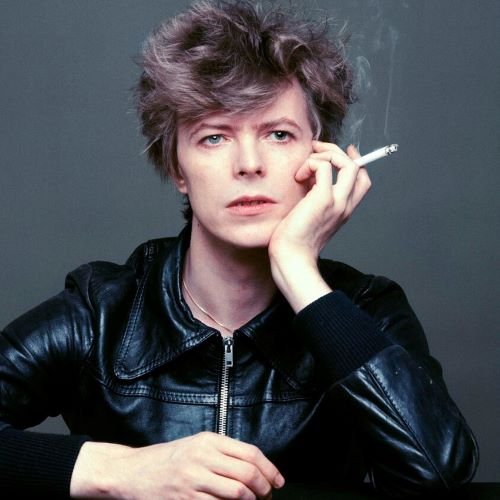

IN THIS PHOTO: David Bowie in 1977/PHOTO CREDIT: Masayoshi Sukita

is the best-known thing from the album, David Bowe’s “Heroes” is one of his best works and one that is coming up for its forty-fifth anniversary. There is an anniversary vinyl coming out that any fan of Bowie’s should get. Released on 14th October, 1977, this was Bowie’s second album that year (the first, Low, came out in January). His twelfth album is one of his classics and defining releases. After releasing Low earlier in 1977, Bowie toured as the keyboardist with Iggy Pop. When the tour wrapped up,, they recorded Pop's second solo album, Lust for Life, at Hansa Tonstudio in West Berlin. After that, Bowie met with collaborator Brian Eno and producer Tony Visconti to record "Heroes". The second part of his Berlin Trilogy – the final being Lodger in 1979 – it was the only one of the three to be recorded completely in Berlin. What is amazing about “Heroes” is that most of the songs’ lyrics were recorded on the spot. The lyrics were pretty much imagined whilst Bowie was in the studio. With a harder, rockier first side and a softer second, there is this great blend of moods and sounds. There have been articles published that rank the tracks on “Heroes”, but I think most people place the title track at the top!

Before coming to a couple of reviews for the classic “Heroes”, there is an article from Classic Albums Sundays gives some background and history regarding the recording of the magnificent “Heroes”. In such a productive year (1977), there is an important to the album. It was the iconic artist bearing his soul and opening his heart. It is a remarkably power listen all these years later:

“After leading many trends of the early ‘70s, “Heroes” found Bowie in a more open and responsive mode. He had submerged himself in the nocturnal culture of Berlin, with its subterranean drinking dens and gaudy drag clubs, taking plenty of inspiration from what he saw and who he spoke to. As Alomar recalled: “I would say that his mental stimulation was at an all-time high at that point. There was a lot of clarity to David, in that he was back to being a literary person, very interested in the politics of the day, knowing the news, which I found amazing because he never cared about that. Obviously, there were other things on his mind than doing his record.”

But despite his Krautrock obsession, Bowie was apparently unmoved by other trends taking the music industry by storm. Released just two weeks after “Heroes” in October 1977, Never Mind The Bollocks immortalised punk rock and the Sex Pistols, but Bowie seemed largely unaware of its impact on youth culture, appearing on TV in leg warmers and a smart blazer as if the news had passed him by completely.“Heroes” mirrored this sentiment by sounding both universal and personal at once. As the album’s marketing slogan summarised: “There’s Old Wave, there’s New Wave and there’s David Bowie.”

Whilst the second half the album is once again occupied by evocative Eno instrumentals such as ‘Moss Garden’ and ‘Neuköln’, it is Bowie’s devastatingly passionate vocal performances for which “Heroes” is most fondly remembered. Having spent hours in the studio with Iggy Pop during his Berlin residency, his own creative approach had begun to mirror the spontaneity of the punk godfather. The only song that had been written prior to the Hansa sessions was ‘Sons of the Silent Age’, with everything else being developed in the recording studio. Bowie often had no idea what lyrics he would be singing until mere moments before he was in front of the microphone. On certain songs, such as ‘Joe the Lion’ his vocals were written and recorded on a line to line basis, with Bowie jotting down consecutive couplets in the booth as he and Visconti pieced together the song with methodical precision.

But other songs took a more conventional approach. During the arduous writing process for the album’s title track, Bowie was suddenly struck by the image of Visconti and his German girlfriend Antonia Maass kissing passionately against the concrete canvas of the Berlin Wall. The romantic view was irresistible, and Bowie was beaming with pride when the pair returned to find he had finally finished the song. Sensing its importance, he and Visconti rehearsed a few times before recording began, deliberating over which point the singer should let loose into the upper octave. In the final recording the sense of anticipation becomes overwhelming. As Bowie sings of nature, royalty, and forbidden love atop Fripp’s soaring guitar lead, the final explosive release ranks among the finest performances of the singer’s career, bristling with an energy that suggests the shedding of a decade’s worth of demons. Captured by three microphones, his voice reverberates around the booth, tracing its boundaries like a prisoner pacing his cell. Before long Bowie is joined by Visconti on backing vocals for a triumphant finale that suggests unity, courage, and reconciliation – symbolism that remains hard to ignore.

Despite the album’s ironic quotation-marked title, “Heroes” marked a moment of genuine soul-searching for Bowie. The Berlin Trilogy as a whole represented a kind of ego-death for the thirty year old star, who had already experienced such unbelievable highs and such crushing lows throughout his most successful decade. The greatest gift the city had given Bowie was its indifference – the war torn metropolis allowed him to be subsumed by its grey concrete and resilient residents; to be a face in the crowd once more. With no costume and no character to play he had regained his perspective and his intuitive sense of what drives ordinary people to do the things they do and love the people they love. To create and release art a mere stone’s throw from a place where a such a privilege was unthinkable without state-censorship was no doubt a humbling experience. The album’s legacy speaks for itself – Bowie’s return to the city in 1987 for a performance of its title-track was hailed as a major catalyst to the later fall of the wall in 1989. Following his death in 2016, the German government expressed its gratitude to a musician whose life-changing experience helped change the lives of so many others: “Goodbye, David Bowie. You are now among Heroes”.

I will finish things off with a couple of reviews. The first, from Pitchfork in 2016, was written in light of Bowie’s passing. It is interesting what they say about Berlin and the environment in which Bowie recorded one of his most celebrated albums:

“Even before David Bowie stepped foot in Berlin's grandiose Meistersaal concert hall, the room had soaked up its fair share of history. Since its opening in 1912, the wood-lined space had played host to chamber music recitals, Expressionist art galleries, and Nazi banquets, becoming a symbol of the German capital's artistic—and political—alliances across the 20th century. The hall's checkered past, as well as its wide-open acoustics, certainly offered a rich backdrop for the recording of "Heroes" in the summer of 1977.

But by then, the Meistersaal was part of Hansa Studios, a facility that felt more like a relic than a destination. Thirty years after much of Berlin was bombed to rubble during World War II, the pillars that marked the studio's exterior were still ripped by bulletholes, its highest windows filled with bricks. Whereas it was once the epitome of the city's cultural vanguard, in '77, the locale was perhaps best known for its proximity to the Berlin Wall—the imposing, barbed-wire-laced structure that turned West Berlin into an island of capitalism amidst East Germany's communist regime during the Cold War. The Wall was erected to stop East Berliners from fleeing into the city's relatively prosperous other half and by the late '70s had been built up to include a no-man's land watched by armed guards in turrets who were ordered to shoot. This area was called the "death strip," for good reason—at least 100 would-be border crossers were killed during the Wall's stand, including an 18-year-old man who was shot dead amid a barrage of 91 bullets just months before Bowie began his work on "Heroes".

All of which is to say: West Berlin was a dangerous and spooky place to make an album in 1977. And that's exactly what Bowie wanted. After falling into hedonistic rock'n'roll clichés in mid-'70s Los Angeles—a place he later called "the most vile piss-pot in the world"—he set his sights on Berlin as a spartan antidote. And though "Heroes" is the second part of his Berlin Trilogy, it's actually the only one of the three that he fully recorded in the city. "Every afternoon I'd sit down at that desk and see three Russian Red Guards looking at us with binoculars, with their Sten guns over their shoulders," the album's producer, Tony Visconti, once recalled. "Everything said we shouldn't be making a record here." All of the manic paranoia and jarring juxtapositions surrounding Hansa bled into the music, which often sounds as if Bowie is conducting chaos, smashing objects together to discover scarily beautiful new shapes.

Those contrasts begin with the album's personnel. For "Heroes", the then-30-year-old enlisted many of the same players that showed up on its predecessor, Low, once again balancing out the effortless groove-based rock stylings of drummer Dennis Davis, bassist George Murray, and guitarist Carlos Alomar, with Bowie's own idiosyncratic work across various instruments along with the heady synth wizardry of Brian Eno, who took on an expanded role. Part Little Richard boogie, part krautrock shuffle, the unlikely stylistic combination hints at man's evolution with technology while throwing off sparks of sweat. Also like Low, the album is broken into two contrasting sides, with the vocal tracks on the front and the back made up of mostly moody instrumentals.

But setting "Heroes" apart was the crucial addition of King Crimson guitar god Robert Fripp, who sprayed his signature metallic tone all over many of the album's most memorable moments. According to legend, Fripp recorded all of his parts in one six-hour burst of wiry bliss and feedback, often just soloing over tracks he was hearing for the first time. That spontaneity—most of the album's jam-based backing rhythm tracks were also recorded quickly, over just two days—is part of what makes "Heroes" live and breathe to this day. It's an album that is constantly morphing, never static. As Fripp's guitar is shooting electrical shocks, Bowie is bleating saxophone blasts, and Eno is summoning sonic storm clouds that pass as soon as they arrive.

And then there are the vocals. "Heroes" contains some of Bowie's greatest vocal performances, fearless takes in which he pushes his voice to wrenching emotional states that often teeter on the edge of sanity. There's tension here, too, because while Bowie is clearly putting all of himself into the microphone like never before, he would often have no idea what he was actually going to sing until actually stepping up to record, a technique borrowed from his frequent collaborator at the time, Iggy Pop. What came out was a Burroughsian stream of consciousness that suggests elements of Bowie's personal travails—involving alcoholism, a crumbling marriage, and business woes—while also sounding abstract and shadowy. He deals with previous alter egos on "Beauty and the Beast," which could be read as a kind of apology for the ill-advised, coke-fueled fantasies of fascism he was peddling just a couple of years before. He muddles sleep and death, dreams and waking life. On the iconic title track, he undercuts the song's would-be heroism by placing its title in quotes; rather than bending over backwards to elevate his own myth, "Heroes" puts everyday courage on a pedestal. It's an immortal track all about fleeting wonders”.

Rolling Stone reviewed “Heroes” when it came out in 1977. Reading a review that reacted to the album at the time it was released, not knowing what was going to come next from Bowie, is fascinating. Maybe not seen as groundbreaking as Low, “Heroes” is an album that is both classic and underrated. I would definitely put the album in Bowie’s top ten:

“Heroes is the second album in what we can now hope will be a series of David Bowie-Brian Eno collaborations, because this album answers the question of whether Bowie can be a real collaborator. Like his work with Lou Reed, Mott the Hoople and Iggy Pop, Low, Bowie’s first album with Eno, seemed to be just another auteurist exploitation, this time of the Eno-Kraftwerk avant-garde. Heroes, though, prompts a much more enthusiastic reading of the collaboration, which here takes the form of a union of Bowie’s dramatic instincts and Eno’s unshakable sonic serenity. Even more importantly, Bowie shows himself for the first time as a willing, even anxious, student rather than a simple cribber. As rock’s Zen master, Eno is fully prepared to show him the way.

Like Low, Heroes is divided into a cyclic instrumental side and a song-set side. “V-2 Schneider” is an ingeniously robotic recasting of Booker T. and the M.G.’s—at once typical of Bowie’s obsession with pop dance music and a spectacular instance of an Eno R&B “study” (a going concern of Eno’s own records). “Sense of Doubt” lines up an ominously deep piano figure with Eno synthesizer washes, blending them into “Moss Garden,” an exquisitely static cut featuring Bowie on koto, a Japanese string instrument. Low had no such moments of easy exchange; Bowie either submitted his voice as another instrument for Eno or he pressed Eno to play the part of art-rock keyboard player.

The most spectacular moments on this record occur on the vocal side’s crazed rock & roll. Working inside the new style Bowie forged for Iggy Pop, “Beauty and the Beast” makes very weird but probable connections between the fairy tale, Iggy’s angel-beast identity and Jean Cocteau’s Surrealist Catholicism, a crucial source for Cocteau’s film of the tale.

For the finale, Heroes explodes into a trilogy of dark prophecy: “Sons of the Silent Age,” “Heroes” and “Black Out.” It’s a Diamond Dogs set that, this time, makes it into the back pages of Samuel Delaney’s post-apocalypse fiction, pushed by a brilliant cerebral nova among the players. Bowie sings in a paradoxical (or is it schizo?) style at once unhinged and wholly self-controlled. With a chill, the listener can hear clearly through Bowie’s compressed lyrics and the dense sound.

We’ll have to wait to see if Bowie has found in the austere Eno a long-term collaborator who can draw out the substantial words and music that have lurked beneath the surface of Bowie’s clever games for so long. But Eno clearly has effected a nearly miraculous change in Bowie already”.

Forty-five on 14th October, David Bowie’s “Heroes” is an album that most people know about, though they may not be aware of much beyond the title track. Containing some of Bowie’s best work, I am glad there is a special anniversary release. Always such a visionary and innovative genius, “Heroes” ranks alongside Bowie’s most moving and revealing work. Even if some critics do not hail and rate the album as high as others in Bowie’s catalogue, I think “Heroes” is amazing. Ahead of its forty-fifth anniversary, go and spend some time with…

A stunning album.