FEATURE:

The Smiths’ Extraordinary Farewell…

Strangeways, Here We Come at Thirty-Five

__________

ON 28th September, 1987…

The Smiths released their fourth and final studio album, Strangeways, Here We Come. There is a lot of debate among fans of the legendary Manchester group as to which album of theirs is the greatest. In this feature, rather than look at the post-Smiths career and discuss Morrissey’s politics etc., this is very much about the band’s final album. I guess most would say 1986’s The Queen Is Dead is the ultimate album by The Smiths. Maybe Strangeways, Here We Come would be third (ahead of Meat Is Murder). Johnny Marr and Morrissey have said their favourite album is Strangeways Here We Come. Not because it was the end and they were keen to get rid of! Rather, this was the genius lyricist (Morrissey) and composer (Marr) combining to deliver some of their very best music. I will come to some features and reviews for a swansong masterpiece. I agree with many who say there are flaws with the album. A couple of weak tracks in the form of Unhappy Birthday and Paint a Vulgar Picture lack wit and depth that we come to expect. That said, there are four or five songs on the album that are peak Smiths. I adore Girlfriend in a Coma, as it is the perfect unity of a funny and tragic Morrissey tale (as the title suggests, he is wondering whether she will make it. We do not know how she got to be in a coma but, as the singer recalls times he could have murdered her, maybe it was him that caused it) and Marr’s upbeat and rousing composition.

I Started Something I Couldn’t Finish is tough and swaggering. As the track fades, Morrissey asks the other Stephen, Street (who co-produced the album), is he wants another take. Death of a Disco Dancer is another humorous song with some rare Morrissey musical input – albeit some rather off-kilter and undisciplined (yet perfectly fitting and great) piano playing. Stop Me If You Think You’ve Heard This One Before, again, is the best of Morrissey and Marr when it comes to wit and great storytelling. I think it is the more emotional songs that hit hardest. I Won’t Share You seems to look at life after The Smiths and the almost brotherly connection between Morrissey and Marr. Even though the band was divided, there is that dependence and respect. The track that I feel should have ended the album (I Won’t Share You does; it would have been perfect just before this) is the epic, sweeping, gorgeous and heart-breaking Last Night I Dreamt That Somebody Loved Me. With a brilliant intro and build of voices and shouts combining, there is this stabbing of strings as Morrissey delivers one of his most affecting, beautiful and heartfelt vocals. The idea of dreaming someone made him safe and put their arms around him only for it to be just “another false alarm” leaves one with questions. Is it literally about being lonely and wanting love? Is it his desire to have safety rather than see The Smiths dissolve? Is it a song about Marr and their strained relationship? I think the favourite song of Morrissey and Marr, this would have been the perfect way to say goodbye!

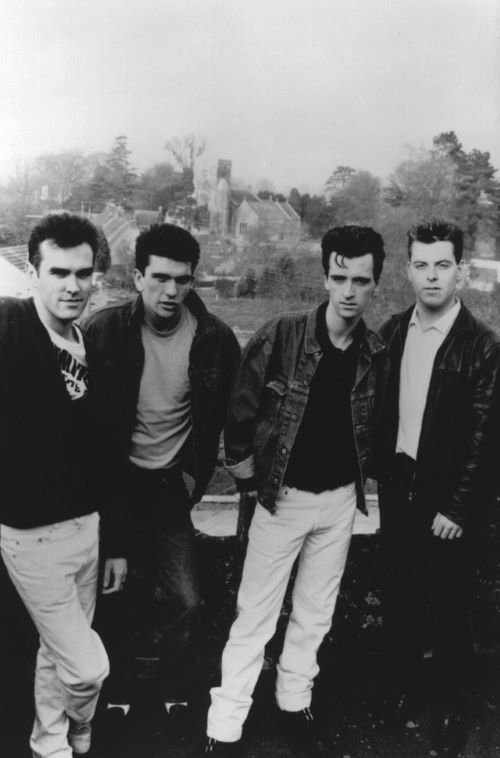

Morrissey, Marr, Andy Rourke and Mike Joyce bowed out with a wonderfully rich and superbly produced album that offered superb variation and nuance. I think that Strangeways, Here We Come is very underrated. Maybe not as consistent as The Queen Is Dead or The Smiths, the strongest songs of the band’s 1987 swansong are unbeatable and timeless! I want to get to a couple of features about Strangeways, Here We Come. In 2012, HUFFPOST talked about the legacy of the album and The Smiths twenty-five years later:

"I'll see you sometime, darling." With these low-key words, and a last caress of Johnny Marr's guitar, the final song on The Smiths' final album ends, dropping the curtain on an extraordinary career. Released 25 years ago today, the last seconds of Strangeways, Here We Come are still enough to make me teary over the loss of one of the most distinctive and beautiful bands in all music, so God knows how it felt for besotted fans when they first heard it in 1987.

Of course, we would see Morrissey again - his solo career was triumphantly launched within an almost indecent six months - but it was indeed the last we would hear from The Smiths. This is one major reason why their legend has grown so vast. While other revered contemporaries have disastrously re-united (hello, Happy Mondays!), or sullenly cashed in (hey, Pixies!), The Smiths - always the stubborn exceptions - have left their legacy untouched.

As a near-lifelong fan, this delights me. No, I'll never see the band perform live, but - having been front row for Morrissey's increasingly erratic solo career, and seen the embarrassment the reformed Sex Pistols heaped upon themselves, eyes wide with pound signs and shame - this is probably a mercy. Besides, The Smiths' passion, originality and beauty are still with us every day, in the extraordinary records they left behind.

Take Strangeways itself. Popular wisdom crowns The Queen Is Dead as their masterpiece, but Strangeways is The Smiths' most ambitious and exciting record. Musically, the band stepped out of the narrow confines of indie pop, starting the album with an entirely guitar-free song before leaping to swaggering glam rock, sinister psychedelica and swirling orchestral epics.

If Johnny Marr was attempting a musical revolution, Morrissey's idiosyncratic worldview remained unshaken: as he sighs during the heartbreaking coda of Last Night I Dreamt That Somebody Loved Me, "this story is old, I know, but it goes on". Yet his romantic desperation has never been as painfully expressed as on this song, nor his sexual frustration so lewdly captured as on I Started Something I Couldn't Finish. Nor was eighties materialism ever skewered more enjoyably than on Paint A Vulgar Picture: "Best of! Most of! Satiate the need!"

Far from a muted epilogue, Strangeways is The Smiths turned up to 11: more heartbroken, witty, lascivious and adventurous than ever before. The explicit politicking may be absent, but this was never as central to The Smiths as the sloganeering album titles suggested: Morrissey was always more preoccupied with romantic than political malaise. There are hundreds of reasons why The Smiths are more loved than the heavily politicised The The (for whom Marr famously moonlighted) but one of them is that Morrissey's lovelorn lyrics were a key which unlocked hearts. Fans admire the furious title track of The Queen Is Dead, but it's "There Is A Light That Never Goes Out" which owns their souls.

In addition to their radiant romanticism, The Smiths won over millions through their ideas (for more on this, go to our current Smiths-celebrating at Pop Lifer). Like all great bands, The Smiths widened our understanding of what pop could be. Morrissey's bedroom-bound years helped him develop a language which is still unique, stitched together from scraps of poetry, sixties kitchen sink melodrama and the deadpan aphorisms of Northern England.

His ambiguous sexuality was also revolutionary: while Duran Duran wielded their heterosexuality like a battering ram and Frankie Goes To Hollywood launched a furious gay counter-attack, Morrissey stayed on the sidelines, a sexual Switzerland. Most Smiths love songs are genderless: of those that are pronouned, they divide fairly evenly between male and female. Arguments still rage over whether Morrissey's disdain for "labels" was helpful to gay teenagers growing up in the awful AIDS era, but his fluid sexuality meant that no-one nursing an aching heart felt excluded from The Smiths' embrace.

Another defining Smiths idea was rejection. From the start they scorned the excesses and materialism that would define the eighties. Where many peers were walking blizzards of hairspray, The Smiths were smartly sculpted, Morrissey's quiff almost architectural. While other bands piled mountains of synths and booming percussion onto every available surface, The Smiths usually pared down, letting Morrissey and Marr's astounding songwriting do the peacocking.

And - amazingly - it worked. By the time Strangeways was released The Smiths had existed for just five years, recording four albums and 73 songs. Of these, only two or three are bad, while most are perilously close to perfect. This unlikeliest of bands had hijacked the UK's charts and were making bold advances into America. More lastingly, they had conquered millions of hearts. And by resisting the fat cheques and desperate pleas to re-unite, they have ensured that no matter what ugly things Morrissey says today, no matter what ordinary music Marr may dabble in, The Smiths' light not only hasn't gone out, it remains undimmed and unsullied”.

The Quietus looked back at Strangeways, Here We Come in 2017. Rather than it being an end, they feel it could have been the start of a new chapter. I wonder what a fifth Smiths studio album would sound like. Perhaps one released in 1989. It would fascinating to think what the band could have produced if they remained stable and got back to how things were in the earlier days! As it is, their final studio album came out on 28th September, 1987:

“But on Strangeways, The Smiths looked forwards, not back, determined to prove their sound was far more nuanced and varied than just Stratocasters and Rickenbackers. That’s why I’ve come to cherish it most of all: it’s my favourite Smiths studio album because it’s the least traditionally Smiths-like, and if the appeal of this band has always partly lain in their obstinacy, then it’s the sound of them blowing a big fat raspberry at their former selves. Whenever history tries to recast them as a bunch of tutting Miss Havishams, it’s the more experimental and ambitious Strangeways that shows their refusal to stay in the past. As Marr later told Goddard: “I wanted us to shed that [old] skin and find a different direction.”

Given that they split before it was even released, it’d be easy to assume the making of Strangeways was plagued by bickering and backstabbing. In truth, their common adversaries at the time were Rough Trade, who they believed had held them back with their lacklustre promotional skills (“Rough Trade cannot quite produce enough testosterone in matters of big business, and they will hold The Smiths back,” was one of Morrissey’s withering assessments of their prowess in his memoir Autobiography). They’d tried, and failed, to finagle themselves out of their deal while working on The Queen Is Dead, leaving them locked in a standoff that delayed its release; by 1986, they’d agreed to jump to EMI, on the proviso they delivered one last album for their old label.

It would be reasonable, too, to think their split was the result of dwindling creativity, but they were making some of their most inventive music yet. Their willingness to try new things on Strangeways, consequences be damned, can even be tracked back to the non-album single ‘Shoplifters Of The World Unite’. Released nine months earlier, it took a typical Smiths motif – an anthem for the downtrodden, a call-to-arms for the oppressed – and gave it an unexpectedly histrionic twist, with Marr’s heavy metal-inspired guitar solo splitting the song in two. By that point, he was unfussed about any potential backlash. “I just went ‘fuck it’, to be honest,” he told tQ ed John Doran in an interview for Noisey in 2013.

There are similar ‘fuck it’ surprises lurking everywhere on Strangeways, just waiting to confuse anyone blithely expecting business as usual. Just listen to the opening songs from their previous albums: the gentle swoon of ‘Reel Around The Fountain’, the familiar jangle of ‘The Headmaster Ritual’, the giddy rush of ‘The Queen Is Dead’. And then listen to the mystical, otherworldly ‘A Rush And A Push', a track that doesn’t ease you in gently but rattles your defences instead: Marr’s piano is eerie and unsettling, and Morrissey’s voice a faint, ghostly wail that echoes like he’s singing through a seance. “Oh hello, I am the ghost of Troubled Joe/ Hung by his pretty white neck some 18 months ago,” he moans.

A couple of lines later, he undercuts the spell by jumping from the unnerving to the humdrum: “There’s too much caffeine in your bloodstream/ And a lack of real spice in your life.” There are Smiths-like tells to be found within its odd, chamber music-like notes: its title, for one, pays homage to Morrissey’s hero Oscar Wilde by lifting a phrase from a pro-Irish editorial published by his mother Lady Jane under her pen name Speranza. And for all its spookiness, it’s the familiar dread of unrequited desire that’s plaguing Morrissey – “Oh don’t mention love/ I’d hate the strain of the pain again,” he sings, only to accept it’s too late by the outro, when he glumly repeats “Oh, I think I’m in love.” But its outright strangeness – the obscure references, the allusions to time travel, the jarring clash between the uncanny and the banal – make it feel like nothing else in their canon. It comes on like a hazy dream or an out-of-body experience; a weird vision that’s already blurry around the edges before it starts slipping out of reach.

Its more experimental tendencies are outdone, though, by the stealthy, slithering electronics of ‘Death Of A Disco Dancer’, a song more magnificently creepy and menacing than anything they’d done before. So many of The Smiths’ most beloved tracks, the ones people typically first fall for, have blistering starts: one of the common threads linking ‘What Difference Does It Make?’, ‘Still Ill’, ‘Never Had No One Ever’, ‘Panic’, ‘This Charming Man’ and ‘There Is A Light That Never Goes Out’ is how quickly they grab you by the gilded beams. But ‘Death’ takes its sinister time, with a slow, dangerous build that imbues Morrissey’s cynicism (“Love, peace and harmony?/ Very nice… but maybe in the next world”) with foreboding. “I don’t talk to my neighbour, I’d rather not get involved,” he sings, and the threat of violence and fear hangs so heavy he doesn’t even need to finish his warning: and if you’ve got any sense, neither will you. Eventually, all its terrible elements – the menacing guitar, the whirring, haunted house-like synth, the crashing drums and Morrissey’s rudimentary, rinky-dink piano (his only instrumental contribution to a Smiths album) – come together in one giant churn of droning, overwhelming noise.

Even some of the album’s more traditional-sounding singles have strange kinks to them: familiar ideas and noises presented in new ways, as if The Smiths have been replaced by doppelgangers who know the old notes but don’t play them in quite the same manner. Marr produced the big “doings” that start ‘Stop Me If You Think You’ve Heard This One Before’, for example, by dropping a metal-handled knife on his Telecaster, getting a strange new sound from a trusty old instrument. Its frantic rhythm and Andy Rourke’s rubbery bass barrel along at the same breathless pace as Morrissey’s gabbered tales, with the singer only occasionally stopping to suck wind before resuming his messy anecdote of sunken pints, broken spleens and shattered promises. By design, its narrator is so slippery it’s hard to pin down exactly why he’s in hospital, but there’s still a perverse thrill in hearing Morrissey, who’d sworn to NME a year previously he’d never do anything as vulgar as have fun, make his voice wobble and waver like he’s half-cut as he unsteadily recalls: “And so I drank one/ It became four/ And when I fell on the floor, I drank more.”

‘I Started Something I Couldn’t Finish’, meanwhile, makes its case not only with Marr’s serrated guitar, but with glammy handclaps and the blaring of a synthesised saxophone. It’s a peculiar stomping beast, full of tight coils of tension and sudden blasts of noise, and made even odder by Morrissey’s performance. In so many Smiths songs, he’s unloved and uncertain, too tongue-tied and limb-locked to take a chance. Here, he’s the clumsy, sweaty pursuer, growling his way into the chorus and forced into repentant retreat when he senses he’s made a mistake. “And now 18 months’ hard labour/ Seems… fair enough,” he shrugs, as if he should have known better, that of course this was bound to happen once he dared to be bold (his punishment is also another nod to Wilde, who received a similar two-year sentence for ‘gross indecency’ in 1895).

It’s the unexpected flourishes that make Strangeways so strong, elevating those songs which might not otherwise have stood out – the bitter barbs and understated semi-acoustic strum of ‘Unhappy Birthday’, for example, are given poignancy by the deep, gorgeous swoon of Marr’s harmonium. There is, in fact, only one track truly beyond redemption, and that’s ‘Girlfriend In A Coma’: the whimsical, unfunny elephant in the room, the one you heartily wish would stop trumpeting its inane jokes. One of the reasons it’s so disappointing is that such a one-note gag feels beneath a band so cunning; the played-for-laughs contrast between the jaunty melody, froggy bass and Morrissey’s wink-wink melodrama as he whispers his last goodbyes is so obvious, it’s like being tricked into sitting on a whoopee cushion by Noel Coward. But it also rankles because whenever people are desperate to prove The Smiths weren’t depressing, it’s songs like these they cling to; the ones so frivolous and farcical you can practically picture Morrissey mugging at you after each line, like he’s in an episode of Miranda. As Simon Reynolds wrote in Melody Maker after their split, The Smiths’ humour worked best when it was “black, scornful, scathing”. Without the piss and vinegar, the biting misery and sourness, it falls flat”.

I am going to finish with a couple of positive reviews for the mighty Strangeways, Here We Come. Thirty-five years after its release, I feel this album warrants retrospection and greater praise. It is a magnificent album from a wonderful group who we lost too soon. This is what AllMusic wrote in their review for Strangeways, Here We Come:

“Recorded as the relationship between Morrissey and Johnny Marr was beginning to splinter, Strangeways, Here We Come is the most carefully considered and elaborately produced album in the group's catalog. Though it aspires greatly to better The Queen Is Dead, it falls just short of its goals. With producer Stephen Street, the Smiths created a subtly shaded and skilled album, one boasting a fuller production than before. Morrissey and Marr also labored hard over the songs, working to expand the Smiths' sound within their very real boundaries. For the most part, they succeed. "I Started Something I Couldn't Finish," "Girlfriend in a Coma," "Stop Me if You Think You've Heard This One Before," and "I Won't Share You" are classics, while "A Rush and a Push and the Land Is Ours," "Death of a Disco Dancer," and "Last Night I Dreamt That Somebody Loved Me" aren't far behind. However, the songs also have a tendency to be glib and forced, particularly on "Unhappy Birthday" and the anti-record company "Paint a Vulgar Picture," which has grown increasingly ironic in the wake of the Smiths' and Morrissey's love of repackaging the same material in new compilations. Still, Strangeways is a graceful way to bow out. While it doesn't match The Queen Is Dead or The Smiths, it is far from embarrassing and offers a summation of the group's considerable strengths”.

The final review I want to include is from Punknews.org. They highlight a couple of flaws but, quite rightly, note how Strangways, Here We Come is magnificent and legendary. I have been revisiting the album a lot preparing this feature. It still moves me now as it did when I first heard it as a teenager:

“In 1986, the Smiths released their best album, The Queen is Dead. This is a scientific fact. It has their best political tune (the title track), their best love song ("There is a Light and It Never Goes Out") and their best song period ("I Know It's Over"). Carried by Morrissey's beautiful, lacerating lyrics and Johnny Marr's shimmering guitar, The Queen is Dead is a great record.

Which is probably why Strangeways, Here We Come, the group's 1987 follow-up, doesn't always get the credit it's due. It's good, but it's not the best Smiths album. It isn't even the best Smiths release from its given year; for us Yanks, that would be the singles collection Louder Than Bombs. Compared to Queen, it's a maudlin, even goofy record. Here is where Morrissey started telling dark stories with a newfound love of camp, either intentionally ("Girlfriend in a Coma," "Death of a Disco Dancer") or not ("Last Night I Dreamt That Somebody Loved Me"). It was a radical shift after Queen's earnest assertions of heavenly ways to die. Indeed, Strangeways is the one Smiths release that could possibly be called "underrated."

I say "possibly" because, well, it's still well-thought of. It's just not quite as celebrated. But at just 36 minutes, it's a thrillingly quick listen. "A Rush and a Push and the Land is Ours" is a haunting opener, all ominous upstrokes and ghosts. "I Started Something I Couldn't Finish" amps up the glam rock undercurrents that Morrissey would cultivate a few months later on his first solo record, Viva Hate. If you wanted to reduce Moz's solo career to a single track, this Smiths cut might do, from the braggadocio, sarcastic vocals to the big, strutting drumbeat.

The record is not without its surprises, though, and the first one is "Death of a Disco Dancer." A solid chunk of the songs on Strangeways are proto-Morrissey solo songs ("I Startedâ¦", "Stop me If You Think You've Heard This One Before," "Paint a Vulgar Picture"), but "Death of a Disco Dancer" is a thunderous tune that builds into a synth-laden frenzy. Morrissey goes on a tangent lyrically ("Love, peace and harmony? / Oh very nice⦠but maybe in the next world"), but it's Marr who dominates here, laying down guitar, synth and piano lines that create a heavenly discordance. No wonder Morrissey still trots this one out live. That the album can then turn to the cheery, airy "Girlfriend in a Coma" makes that noise that much more apparent.

Strangeways is an album of big rock moves. These songs are among the group's catchiest. They even trot out studio tricks like strings for fun. But the album also packs some pleasing left turns. "Stop Me If You Think You've Heard This One Before" is the most Smiths-y, as its driven by Marr's trademark jangley guitar work, but it's pleasantly out of place here. Same for "Unhappy Birthday."

Ah, but the best track is the last one. "I Won't Share You." It's the simplest song, driven primarily by Marr on autoharp. It's the most haunting, especially when the reverb kicks in. And it also, in a way, feels like the one completely genuine track on the record. Morrissey doesn't mask his intentions in camp and sarcasm. Oh sure, it's still got some of his wit ("Has the Perrier gone straight to my head?") and ego ("I won't share you / With the drive / And the dreams inside / This is my time"), but it's such a beautifully performed song.

Strangeways has a lot going for it, and a lot of baggage to bear. Because it followed The Queen is Dead. Because it's the last Smiths record. Because "Last Night I Dreamt That Somebody Loved Me" is kind of cheesy. Despite these things, it's still a phenomenal record”.

The lush, funny, bittersweet and incredibly brilliant Strangeways, Here We Come is thirty-five on 28th September. An album that, to me and many others, ranks there with the best of The Smiths, I hope it gets love and celebration when we mark thirty-five years of its existence. Kudos to Stephen Street for some phenomenal production work, at a time that must have been quite tense! Maybe we misperceive The Smiths’ final days like we used to with The Beatles, but it would have been a less harmonious studio environment compared to Earlier work from the band. Maybe Johnny Marr and Morrissey felt they needed another producer to help keep things together. Maybe someone to act as a buffer when needed. Regardless, Strangeways, Here We Come is a classic that should get all the respect in the world. Maybe it would have been impossible for The Smiths to continue, but their splendid fourth studio album suggests they could have continued. It is a classic case of…

WHAT could have been.