FEATURE:

Sublime!

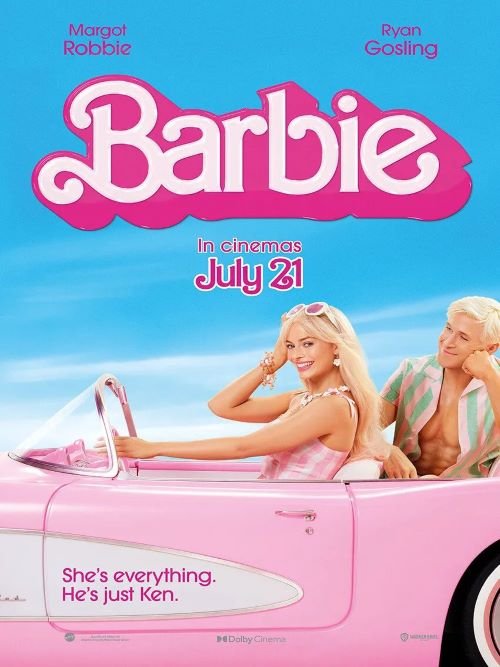

IN THIS PHOTO: Barbie’s director and co-writer (with her partner Noah Baumbach) Greta Gerwig/PHOTO CREDIT: Leeor Wild/The Observer

My Favourite Film of 2023: Barbie

_________

THIS may seem unrelated to music…

but there is a musical connection when it comes to Barbie. Released on 21st July, it was a huge box office success that saw it take over $1bn. Its director Greta Gerwig was named the first female director to achieve that feat. Its soundtrack is also pretty awesome! In fact, a couple of songs from the film, Billie Eilish’s What Was I Made For?, and Dua Lipa’s Dance the Night, are both nominated at next year’s GRAMMY Awards for Song of the Year. I think Taylor Swift will win that category for Anti-Hero, though Ryan Gosling (who played Ken in the film) is nominated for I’m Just Ken – which is in the Best Song Written For Visual Media (that also sits alongside three other songs from Barbie, so it seems a shoo-in the film will win at least one GRAMMY!). What Was I Made For? is also nominated for Best Music Video (directed by Billie Eilish), whilst the soundtrack is nominated in the Best Compilation Soundtrack For Visual Media category. Dominating the GRAMMYs, there is that strong musical connection. I think one reason why it is so well-represented at the GRAMMY Awards is the beauty of the film. The direction and placement of the songs is perfect. The script, written by Greta Gerwig and Noah Baumbach, captivated audiences. Starring Margot Robbie as the titular character (Stereotypical Barbie, to be precise!), Barbie was a phenomenal success. It gives me a chance to explore it one final time for this year. As the strikes are over in Hollywood, there is going to be campaign ahead of award season next year. Further promotion that was not permitted months ago. I want to get to some interviews and reviews, just to give you a feeling of why Barbie was so celebrated and has been this once-in-a-lifetime experience. I will drop the soundtrack in, plus some clips and various bits and pieces.

Before coming to any of that, I want to give general impressions. I also love Celine Song’s Past Lives. In terms of filmmaking this year, female directors and writers have produced some of the most startling and memorable films. I know we shouldn’t be dividing by gender and talking in those terms though, at a time when there is not full recognition of women in Hollywood, the fact is that Greta Gerwig, Celine Song and so many other amazing women have created masterpieces needs to be recognised and resonate – and I hope that is reflected at award ceremonies. I do think that Barbie is going to get nominated for at least four Oscars. For set design and costumes. Greta Gerwig seems certain to be nominated for Best Director. One hopes that Margot Robbie is nominated as Best Actress. Maybe Ryan Gosling will get nominated as Best Actor? I think the screenplay for Barbie is phenomenal, though that is a tough category so it may not get nominated. We know that, prior to the 21st July release, Barbie was pitted against Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer. They came out on the same day. Even though they are very different films, there was this ‘Barbenheimer’ phenomenon that nobody thought we’d see in modern cinema! Almost this cultural moment where people were celebrating cinema and there was this deep fascination with two sensational filmmakers. Oppenheimer will also get a lot of Oscar recognition – including Best Director for sure -, yet Barbie has been the big cinema winner this year. My favourite film by far, it is one that I have discussed and dissected so many times. I do feel that a documentary or book about Barbie is warranted. Charting its inception, promotion and impact. It genuinely is one foy those generational highpoints that needs to be celebrated and discussed as much as possible.

I will come to a review of Barbie in a minute. I will end by a recent feature/piece about the film and its success. It is worth focusing on interviews with Greta Gerwig (Noah Baumbach was not really involved with any promotion) and Margot Robbie. I am going to source from an interview they each did separately. Gerwig, as the director coming from Indie cinema who wrote/directed her first ‘major’ motion picture, was very much in the spotlight. This wonderfully colourful and imaginative transition. Margot Robbie, who bought the rights to Barbie and brought the idea to Gerwig, taking on her most high-profile and biggest role to date. In July, The Guardian published an interview with Greta Gerwig. This was a film, as she said, that had to be “totally bananas”:

“One night in April, a stranger I met in a pub pulled out his phone and showed me pictures of something he was working on. We were in a town near to the Leavesden film studios, where the stranger had been constructing sets for Barbie, a film co-written and directed by the American filmmaker Greta Gerwig. “You have to see this,” the man said, before presenting images of a hot-pink, human-sized Barbieland, a place he described as an antidote to our hideously cold winter. Rain was forecast the following day, and even colder cold, but the stranger couldn’t care less. He would be a world away.

When I tell Gerwig this story, over Zoom, one day in June, her large eyes brighten. “That makes me feel like a proud mama!” she says, and, “Gosh, that makes me tear up.” Over the hour we spend together, while she sits in Manhattan, in a room she describes as “half office, half baby nursery,” this is the kind of pronounced buoyancy I come to expect from her. Even when I suggest the stranger perhaps shouldn’t have shown me the pictures – the set being locked down, me being a journalist – Gerwig says, in a wink-wink tone, “But I love that he felt he wanted to.”

Gerwig was invited to write Barbie by the actor Margot Robbie who, with Warner Bros, had bought the rights to the film. (Robbie stars in Barbie as Barbie.) Gerwig has said she was terrified to accept the job. “It’s not like a superhero, who already has a story. It felt very much like it was going to be an adaptation. Except what we were adapting is a doll – an icon of the 20th century.” Before writing the script, Gerwig thought: “It felt complicated enough, sticky enough, strange enough, that maybe there could be something interesting there to be discovered.” She didn’t know she was going to direct the film until after the script was written. “I kind of had two thoughts: I love this and I can’t bear it if anyone else makes it. And: they’ll never let us make this movie.”

PHOTO CREDIT: Leeor Wild/The Observer

To pitch Barbie to executives, Gerwig wrote a poem so strange and “surreal” that she will not read it to me now. When I ask what it concerned, she says, “Oh, you know, the lament of Job?” before adding, “Shockingly, it does actually communicate some vibe of the movie.” Gerwig wrote Barbie with her partner, the filmmaker Noah Baumbach, though for a while she didn’t tell him she’d enlisted his help. (“He was like, ‘Did you sign us up to write a Barbie movie?’ And I was like, ‘Yes, Noah, get excited!’”) They worked on the script during the pandemic, when doubt plagued the future of the communal cinema experience. “There was this sense of wanting to make something anarchic and wild and completely bananas,” Gerwig says, “because it felt, like, ‘Well, if we ever do get to go back to cinemas again, let’s do something totally unhinged.’” The anarchy of Gerwig’s Barbie comes from “the deep isolation of the pandemic,” she says – “that feeling of being in our own little boxes, alone.”

I like people. It’s one of the reasons I like living in New York City. I wouldn’t do well alone in the woods

Such are the levels of secrecy around Barbie that I was only allowed to watch the first 20 minutes of the film, which I did in a large screening room, alone but for a projectionist, a Warner Bros employee, and a man who sealed my phone in an opaque bag. Watching 20 minutes of a film is not enough to say if it is good or not, but it is enough to confirm an early vibe, which is anarchic. There is colour and artificiality, fun and chaos. There are many Barbies and many Kens. It has the atmosphere of an over-the-top gender-reveal party during which various things go wrong. Barbie’s feet become flat, not stiletto-arched. Her shower runs cold. Her breakfast burns. She develops neuroses. A once perfect-seeming life becomes not perfect.

Partway through an elaborate, multi-cast dance number, Robbie asks, suddenly: “Do you guys ever think about dying?” Gerwig thinks of this line as being demonstrative of the film’s anarchic energy. When I ask in what other ways the film is anarchic, she replies, not quite answering the question, “Oh. This movie is crazy.”

I ask her to describe it. “There were so many ways to go into it,” she says, before listing some. “The idea of Barbieland. The idea of Barbie herself being constrained in multitudes. The idea that self is dispersed among many people, that all of these women are Barbie and Barbie is all of these women. That’s pretty trippy to begin with. And the sense that she is continuous with her environment. That there really is no internal life, at all. Because there is just no need to have an internal life.”

Barbie was conceived in 1959, by Ruth Handler, who co-founded the doll’s manufacturer Mattel. Barbie has since occupied a complicated position in the lives of her owners. On one hand, she has been terrible for girls’ body image, a fact Gerwig acknowledges playfully in the film’s opening 20 minutes. (On discovering Barbie’s flat feet, several other Barbies, and at least one Ken, heave mawkishly and knowingly in disgust.) But according to fans she has empowered, too. In more recent times, Mattel has produced dolls with different skin colours and in different shapes. While researching Barbie, Gerwig toured the company’s headquarters. “The kind of amazing thing is that Barbie went to the moon before women had the ability to get credit cards,” she says. “That’s crazy. She was always a kind of step ahead.”

At Mattel, Gerwig saw an image of an all-female Barbie presidential ticket. “I was like, ‘Huh, so Barbie’s done it, but we haven’t?” (The first presidential Barbie appeared in 1992; in the film, president Barbie is played by Issa Rae.) Gerwig was fascinated. “As an icon, she’s always been complicated,” she says. “She has always had these two sides to her.”

Growing up, Gerwig had a tangled relationship with the doll. “I was always intrigued,” she says, because, “Barbie was, if not exactly forbidden in our house, well, it was not encouraged.” Why not? “Oh, the usual criticisms. ‘If she was a real woman, she wouldn’t even be able to stand up; she wouldn’t be able to support her head.’ My mum was a child of the 60s. She was like, ‘We got this far, for this?’” Eventually, Gerwig’s mother relented. “She got me my own,” Gerwig recalls. “Fresh out the box.” It replaced the neighbourhood hand-me-downs she had been playing with.

But Gerwig already had a strong connection to other dolls, the kind you mother, and she had a vivid imagination. “I played with dolls until… I don’t want to say too late, but I played with them long enough that I didn’t want kids at school to know I still played with them. I was a teenager. I was about 13 and still playing with dolls. And I knew that kids at that point were already kissing.” She smiles. “I was a late bloomer.”

Gerwig has said that Barbie’s story mimics that of a girl’s journey from childhood to adolescence. “I always think that 8, 9, 10 years old is peak kid. I was brash and unafraid and loud and big. And then, you know…” Puberty. “It’s a shrinking. Wanting to make yourself smaller, less noticeable, take in all that spikiness and bury it. And you’re profoundly uncomfortable, because you’re going through metamorphosis, literally.” You begin to introspect. “But also, you’re getting tall. You’re getting your period. You get spots.” Gerwig describes childhood as being at peace with the world and adolescence as being suddenly not. “My experience of it was wanting to hide.”

I ask, “Is the film about growing up?”

“It’s not about growing up, exactly,” she says. “But in a way… This is about Barbie, an inanimate doll made out of plastic. But the movie ends up, really, about being human.”

I had two thoughts: I love this and I can’t bear it if anyone else makes it. Barbie went to the moon before women had the ability to get credit cards

In many ways, the themes in Barbie chime with those Gerwig has tackled previously, not least in Lady Bird, her loosely autobiographical directorial debut, and a 2019 adaptation of the Louisa May Alcott novel, Little Women, which the critic Anthony Lane said, “may just be the best film yet made by an American woman”. Both films star Saoirse Ronan and feature adolescent women becoming new, more complicated versions of themselves. Gerwig was nominated for best director at the Oscars for Lady Bird – she became only the fifth female director to be nominated for the award. If Lady Bird announced Gerwig as a top-tier filmmaker, Little Women confirmed it. Plaudits followed. Hollywood invited her in. But Barbie is different altogether: bigger budget, bigger anticipation – what might be the first true summer blockbuster, post-pandemic. When I ask Gerwig how she feels about the film’s release, she says, “I’m just so nervous. I’m so nervous. I’m excited! But I’m so nervous.” And then: “I just can’t believe, like, here it is… Let’s go!”

PHOTO CREDIT: Leeor Wild/The Observer

Before filming, Gerwig organised a Barbie sleepover at Claridges, the London hotel, and invited a number of the film’s female cast: Robbie, Rae, America Fererra. The Kens were invited, but asked not to spend the night; the Barbies wore pyjamas and played games. “Honestly, it just felt like it would be the most fun way to kick everything off,” Gerwig says. “And it’s something you don’t get to do that much as an adult. Like, ‘I’m just going to go have a sleepover with my friends…’”

Gerwig is known for creating open, democratic sets. And she describes part of her job as “creating an atmosphere of acceptance, no wrong answers, no judgment. It allows people to feel safe, to bring wonderfully wild things to the table, which they otherwise might not want to.” (“She’s into things arising,” the actor Jamie Demetriou, who appears in Barbie, told me.) That everyone on set bonds is important to Gerwig – hence the sleepover. Before Little Women, she asked the film’s primary cast – Ronan, Florence Pugh, Emma Watson and Eliza Scanlen – to memorise a poem, and to later recite it to each other. “These were professional actors,” Gerwig recalls, “but there was something about the fact they had to select a poem and then recite it… It was very intimate and amazing, and they were very vulnerable. It instantly felt helpful in creating that connection.” She later adds: “As a director, you have the job of dreaming up the movie, and then you have to get everyone else in the movie – hundreds of people – to have that same dream, too.”

Demetriou recalls the Barbie set being full of positivity. “A lot of the film I spent with Will Ferrell and Connor Swindells talking about how there was this magical drip-down effect from her,” he told me, “this positive vibe that everyone wanted to keep going”.

There is no doubt that Margot Robbie’s turn as Barbie/Stereotypical Barbie is the standout turn. Full of nuance, emotion, comedy, vulnerability and passion, it is a breathtaking performance! The fact is that she recognised there was potential to turn Barbie into a film and make it impactful and important. She identified Greta Gerwig – who she had worked alongside before – as someone who could make it a reality. Lesser filmmakers might have turned thew film into pure fantasy or something misjudged. Greta Gerwig’s handling means that you get the superficial and plastic alongside the real world. That hit of realisation when Barbie steps from Barbie Land to the real world and realises that things are not perfect; that men hold all of the power instead. Many thought the film had a bad feminist message and was attacking men. Neither is true. So many wrong-headed features were written about the film – many by The Guardian; the same publication that did such a wonderful interview with Gerwig -, whilst so many others did not get the point or see the full potential of the film. Objectively, Barbie definitely warranted four and five-star reviews right across the board. There were many who were much less favourable. I know film is subjective, yet there was a lot of undue criticism and misinterpretation. Most agreed on one thing, however: Margot Robbie’s performance was sensational (or, to quote Ken, “Sublime!”). In May, Margot Robbie spoke with Vogue about Barbie. I want to quote where she discusses bringing the idea to Greta Gerwig. What Gerwig’s set was like:

“LuckyChap wanted Gerwig and Baumbach to have full creative freedom. “At the same time,” Robbie says, “we’ve got two very nervous ginormous companies, Warner Bros. and Mattel, being like: What’s their plan? What are they going to do? What’s it gonna be about? What’s she going to say? They have a bazillion questions.” In the end LuckyChap found a way to structure a deal so that Gerwig and Baumbach would be left alone to write what they wanted, “which was really fucking hard to do.”

Gerwig and Baumbach did share a treatment, Robbie adds: “Greta wrote an abstract poem about Barbie. And when I say ‘abstract,’ I mean it was super abstract.” (Gerwig declines to read me the poem but offers that it “shares some similarities with the Apostles’ Creed.”) No one at LuckyChap, Mattel, or Warner Bros. saw any pages of the script until it was finished.

PHOTO CREDIT: Ethan James Green for Vogue

When I ask Gerwig and Baumbach to describe their Barbie writing process, the words “open” and “free” get used a lot. The project seemed “wide open,” Gerwig tells me. “There really was this kind of open, free road that we could keep building,” Baumbach says. Part of it had to do with the fact that their characters were dolls. “It’s like you’re playing with dolls when you’re writing something, and in this case, of course, there was this extra layer in that they were dolls,” Baumbach says. “It was literally imaginative play,” Gerwig says. That they were writing the script during lockdown also mattered, Baumbach says. “We were in the pandemic, and everybody had the feeling of, Who knows what the world is going to look like. That fueled it as well. That feeling of: Well, here goes nothing.”

Robbie and Ackerley read the Barbie script at the same time. A certain joke on page one sent their jaws to the floor. “We just looked at each other, pure panic on our faces,” Robbie recalls. “We were like, Holy fucking shit.” When Robbie finished reading: “I think the first thing I said to Tom was, This is so genius. It is such a shame that we’re never going to be able to make this movie.”

LuckyChap did make the movie, of course, and it’s very much the one Gerwig and Baumbach wrote. (Alas, that joke on page one is gone.) If you saw the trailer released in December, you’ve seen the opening of the film. It’s a parody of the Dawn of Man sequence from 2001: A Space Odyssey. But instead of apes discovering tools in the presence of a monolith, little girls smash their baby dolls in the presence of a gigantic Barbie. Robbie-as-Barbie appears in a retro black-and-white bathing suit and towering heels. She slowly lowers a pair of white cat-eye sunglasses and winks.

PHOTO CREDIT: Ethan James Green for Vogue

I saw more of the movie one morning at the Warner Bros. lot. After the Kubrick spoof we go on a romp through Barbieland, “a mad fantasy of gorgeousness,” as Sarah Greenwood, the film’s set designer, puts it later. Barbie wakes up in her Dreamhouse and embarks on the Perfect Day, accompanied by an original song that serves as soundtrack. (I am not allowed to say who sings it.) Everything everywhere is infused with pink. “I’ve never done such a deep dive into pink in all my days,” Greenwood says. Barbie’s perfectly fake, color-saturated world retains many of the quirks and physical limitations of the toy version. Her environment isn’t always three-dimensional, and the scale of everything is a bit off. Barbie is a little too big for her house and her car. When she takes a shower, there is no water. Her bare feet remain arched.

The swimsuit Robbie wears in the Dawn of Woman sequence is a replica of the one worn by the first Barbie doll in 1959. Over the course of the Perfect Day, Barbie changes clothes constantly. The progression—poodle skirt, disco look—amounts to a survey of Barbie fashion over time, says Jacqueline Durran, the film’s costume designer. (Wisely, the survey does not include the more retrograde outfits in Barbie’s past, such as the Slumber Party ensemble of 1965, which came with a little bathroom scale set at 110 pounds and a book titled How to Lose Weight that advised: “Don’t eat.”)

“The key thing about Barbie is that she dresses with intention,” Durran tells me. “Barbie doesn’t dress for the day. She dresses for the task.” The task might involve a leisure activity, or a form of employment. One scene pokes fun at the way the Barbie universe seems to blur such distinctions. “My job is just beach,” Ken explains.

Ken is played with daft aplomb by Ryan Gosling. “The greatest version of Ryan Gosling ever put on screen,” in Robbie’s estimation. (Gosling: “Ken wasn’t really on my bucket list. But in fairness, I don’t have a bucket list. So I thought I’d give it a shot.”) In Barbieland, Ken is basically another fashion accessory. “Barbie has a great day every day,” we are told in voiceover delivered by Helen Mirren. “Ken only has a great day if Barbie looks at him.” Mattel introduced the first Ken doll in 1961, in response to letters demanding Barbie get a boyfriend. “Barbie was invented first,” Gerwig points out. “Ken was invented after Barbie, to burnish Barbie’s position in our eyes and in the world. That kind of creation myth is the opposite of the creation myth in Genesis.”

Just as Barbie was given big boobs but no nipples, Ken was given a smooth “bulge,” as Mattel referred to it at the time. Together, their peculiar partial anatomy hints at a world of grown-up things hidden from view. Gerwig: “You feel that there’s something there, which is part of the allure. It’s unclear how this all kinda works. But it’s not without intrigue.” This vague sense of mystery is captured in a comical exchange Ken and Barbie have in front of her Dreamhouse. “I thought I might stay over tonight,” Ken says. “Why?” Barbie asks. “Because we’re girlfriend-boyfriend,” Ken says. “To do what?” Barbie asks. “I’m actually not sure,” Ken says.

“The key thing about Barbie is that she dresses with intention,” says Jacqueline Durran, the film’s costume designer. Jacket, top, skirt, belt, shoes, and tights, all Saint Laurent by Anthony Vaccarello.

Barbie acquired friends over the years. First came Midge, her longtime best friend, and later Christie, one of her first Black friends. (Mattel didn’t introduce a Black Barbie until 1980, and a forthcoming documentary, Black Barbie, explores this legacy.) When Gerwig took a tour of Mattel, she learned that the vast majority of dolls in its Barbie line are named Barbie. “Now all of the dolls are Barbie. All of them are Barbie, and Barbie is everyone. Philosophically, I was like, Well, now that’s interesting.” The more she thought about it, the more the multiplicity of Barbies suggested “an expansive idea of self that we could all learn from.”

PHOTO CREDIT: Ethan James Green for Vogue

During the casting process, Gerwig and Robbie looked for “Barbie energy,” a certain ineffable combination of beauty and exuberance they concluded is embodied in Gal Gadot. Robbie: “Gal Gadot is Barbie energy. Because Gal Gadot is so impossibly beautiful, but you don’t hate her for being that beautiful, because she’s so genuinely sincere, and she’s so enthusiastically kind, that it’s almost dorky. It’s like right before being a dork.” (Gadot wasn’t available.) They found their Barbies in Issa Rae, Hari Nef, Emma Mackey, Dua Lipa, Sharon Rooney, Ana Cruz Kayne, Alexandra Shipp, Kate McKinnon, and others. (There are multiple Kens too.) In this menagerie, Rae is President Barbie. Robbie is Stereotypical Barbie.

Before shooting began in London, Gerwig threw a slumber party for the Barbies at Claridge’s Hotel. The Kens were invited to stop by, but not to sleep over. (Gosling couldn’t make it, so he sent a singing telegram in the form of an older Scottish man in a kilt who played bagpipes and delivered the speech from Braveheart.) Once production was underway, LuckyChap hosted weekly movie screenings at the Electric Cinema in Notting Hill. Every Sunday morning, cast and crew were invited to watch a movie that served as a reference for Barbie. They called this “movie church.”

Gerwig had a sense that Barbie was being guided by old soundstage Technicolor musicals, so they watched a bunch of those, most helpfully The Red Shoes and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg. “They have such a high level of what we came to call authentic artificiality,” Gerwig says. “You have a painted sky in a soundstage. Which is an illusion, but it’s also really there. The painted backdrop is really there. The tangibility of the artifice is something that we kept going back to.” Her director of photography, Rodrigo Prieto, who shot The Wolf of Wall Street and Babel and Argo and Brokeback Mountain, created a special color template for Barbie with this in mind. Gerwig named it Techni-Barbie”.

Before coming to a final feature, I want to come to one of the most positive reviews for Barbie. The Independent (quite rightly) awarded it five stars. I feel like they got to the heart of the film like few others. Not over-analysing or giving bad takes. Not focusing on commercialism, ‘bad feminism’ or anything that takes away from the remarkable achievements of Greta Gerwig et al. Barbie is one for the cinematic history books:

“Barbie is one of the most inventive, immaculately crafted and surprising mainstream films in recent memory – a testament to what can be achieved within even the deepest bowels of capitalism. It’s timely, too, arriving a week after the creative forces behind these stories began striking for their right to a living wage and the ability to work without the threat of being replaced by an AI. It’s a pink-splattered manifesto to the power of irreplaceable creative labour and imagination.

While it’s impossible for any studio film to be truly subversive, especially when consumer culture has caught on to the idea that self-awareness is good for business (there’s nothing that companies love more these days than to feel like they’re in on the joke), Barbie gets away with far more than you’d think was possible. It’s a project that writer-director Greta Gerwig, co-writer (plus real-life partner and frequent collaborator) Noah Baumbach, and producer-star Margot Robbie were free to work on in relative privacy, holed up during the pandemic away from the meddlesome impulses of Warner Bros and Mattel executives.

The results are appropriately free-wheeling: There are nods to Jacques Demy’s The Umbrellas of Cherbourg and Jacques Tati’s Playtime, deployment of soundstage sets and dance choreography à la Hollywood’s musical Golden Age, and a mischievous streak of corporate satire that calls to mind 2001’s cult classic Josie and the Pussycats. But while the absurdity of its humour sits somewhere between It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World and Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, its earnest and vulnerable take on womanhood is pure Gerwig, serving as a direct continuation of her Lady Bird and Little Women.

The fact that all of this is tied to one of the most recognisable products in existence – and that any success it enjoys will undoubtedly boost Mattel’s stock prices – underlines the fact that it’s largely impossible to embrace art without embracing hypocrisy. Capitalism doesn’t always swallow art whole; occasionally it thrives in spite of it. And that’s a complexity that feels particularly on brand for a director who had her Jo March, in Little Women, declare: “I am so sick of people saying that love is just all a woman is fit for. I’m so sick of it! But – I am so lonely.”

Barbie contains another Gerwig-ian speech, delivered beautifully by an ordinary (human) mum played by America Ferrera, about the hellish trap women have been forced into. Caught between girl-boss feminism and outright misogyny, women now have to be rich, thin, liberated, and eternally grateful without ever breaking a sweat – because when Barbie promised little girls that “women can be anything”, those words got twisted to mean “women should be everything”. Gerwig’s movie begins by playing a brilliant trick on its audience: Helen Mirren’s opening narration is self-congratulatory, a bit of canned PR about Barbie’s “girl power” legacy that grows increasingly tongue-in-cheek. “Thanks to Barbie,” she concludes, “all problems of feminism and equal rights have been solved”.

We’re then introduced to our Barbie – ie “the Stereotypical Barbie” – who is chipper, confident, blonde, and, most importantly, looks like Margot Robbie. She is eternally adored by Ken (Ryan Gosling), whose job is “beach”. Not “lifeguard”, but “beach”. Barbie’s friends all have high-powered jobs: president (Issa Rae), author (Alexandra Shipp), physicist (Emma Mackey), doctor (Hari Nef), and lawyer (Sharon Rooney). Every morning, she steps into her shower (there’s no water), sets out her breakfast of a heart-shaped waffle with a dollop of whipped cream (she doesn’t eat), and then sets off in her pink convertible (she doesn’t walk downstairs, but merely floats). All is perfect. Then Barbie starts having irrepressible thoughts of death.

Barbie’s bid to fix that sudden, scary attack of humanity sees her visit “the Real World”, where she meets the all-male executive board of Mattel (among them Will Ferrell and a wonderfully dorky Jamie Demetriou), who think themselves qualified to determine what little girls like and need because they once had a woman CEO (or two, maybe). Meanwhile, Gerwig uses, through a hysterical farce centred around Gosling and his fellow Kens, the implicit matriarchy of Barbieland to explore how power and visibility shape a person’s self-perception. Gosling gives an all-timer of a comedic performance, one that’s part-baby, part-Zoolander, part-maniac, and 100 per cent a validation for anyone who ever liked him in 2016’s noir comedy The Nice Guys. There are (naturally) some exquisite outfits designed by Jacqueline Durran, some very funny references to discontinued Barbies (have fun reading up on the backstory behind Earring Magic Ken), and a few unexpected pops at fans of Duolingo, Top Gun, and Zack Snyder’s Justice League.

Barbie is joyous from minute to minute to minute. But it’s where the film ends up that really cements the near-miraculousness of Gerwig’s achievement. Very late in the movie, a conversation is had that neatly sums up one of the great illusions of capitalism – that creations exist independently from those that created them. It’s why films and television shows get turned into “content”, and why writers and actors end up exploited and demeaned. Barbie, in its own sly, silly way, gets to the very heart of why these current strikes are so necessary”.

It must have been a shock for Greta Gerwig. We have not even got to award season yet. In terms of the box office and the worldwide reaction to Barbie, it has been a dream! A successful and acclaimed actor and director, Gerwig triumphantly transitioned from smaller Indie films – though Oscar-nominated Lady Bird (2017) and Little Women (2019) were huge successes – to this massive and all-conquering multi-million-dollar film of a very recognisable figure. It could have gone wrong or a massive failure. As it was, Barbie exceeded all expectation! I will end with a BBC article that reacted to Greta Gerwig speaking at the London Film Festival in October. She weas blown away and moved hugely by the reaction to Barbie:

“Greta Gerwig, the director of smash hit movie Barbie, has described the film's success as "so moving".

The blockbuster follows the famous doll and her companion Ken travelling from Barbieland into the real world.

Gerwig, speaking at the London Film Festival, added that seeing the movie being enjoyed by so many had been "the most thrilling thing".

The film has taken $1.44bn (£1.2bn) at the box office, making her the most successful solo female director ever.

The director was in conversation at the festival with Peep Show co-creator and Succession writer Jesse Armstrong.

Such joy

Speaking about the months she spent working on Barbie, she told him: "The process of making it was such joy. It was the most joyful set I've ever been on.

"I thought, if I can make a movie that's half, or [a] quarter as fun to watch as it was to make, I think maybe we've got a shot."

It was released in July, and Gerwig went into cinemas to see the reaction and ensure audiences had the best viewing - and listening - experience, she revealed.

"On the opening weekend I was in New York City. And I went around some different theatres and sort of stood in the back. And then also turned up the volume if I felt it was playing at maybe not the perfect level," she said. "It was the most thrilling thing."

IN THIS PHOTO: Greta Gerwig on stage at the London Film Festival/PHOTO CREDIT: Getty Images

She told film fans at the London festival that she'd grown up loving watching films in movie theatres.

"And I think that part of me always wanted to recreate that feeling from childhood of meeting in a dark room with a bunch of people. So it was so moving to me that that was the thing that people experienced."

She also thanked the BBC for allowing her to use a short extract from its 1995 TV adaptation of Pride & Prejudice in her film.

"I was very honoured they said yes to that," she said. "That was a big deal. They don't always say yes. Thank you to Jennifer Ehle and Colin Firth, that was very lovely."

And although she was careful not to name it, Gerwig also spoke briefly about her next, eagerly awaited project, and the challenges it's presenting.

"I'm working on something right now, I'm in the writing process," she told the audience. "And it's hard. And I'm having nightmares. I'm having recurring nightmares”.

My favourite film of the year – and one of my favourites of all time -, there are going to be new eyes on Barbie next year. It will be nominated for scores of awards without question. I hope Greta Gerwig, Margot Robbie and everyone involved gets to speak about the film (and what would have been a wonderful experience for all). The GRAMMY Awards on 6th February will be interesting. With so many of the songs nominated (Lizzo’s Pink was omitted, one suspects, due to allegations made against her earlier this year), Barbie will cross from film into music. In any case, the musical recognition of Barbie shows that it is a film that has conquered and seduced everyone! Such a remarkable film from an iconic and hugely important filmmaker who has broken records and helped to bring to life this astonishing film, everyone who has not seen Barbie needs to check it out (it is available through Prime Video). I am not quite sure what Greta Gerwig and Margot Robbie are releasing next and whether they will come together again. I hope that there is another collaboration, as they are so close and have this immense respect for one another! That shows when you watch Barbie. It is a film that created a phenomenon and explosion of cheer and pink at cinemas and theatres across the world. It is an explosion and cultural moment that we will never…

SEE the like of again.