FEATURE:

You Cut Along a Dotted Line

IN THIS PHOTO: Kate Bush in 2005/PHOTO CREDIT: Trevor Leighton

Placing Kate Bush’s Singles, Albums and the Ten Best Videos

_________

THIS might be something that…

IN THIS PHOTO: Kate Bush in 1985/PHOTO CREDIT: Guido Harari

other people do if Kate Bush announces a new album. You do get features that rank her singles, albums and songs in general. It usually comes off of the back of some bit of news or something new being released. I am going to move on to rank her studio albums, as my opinions have changed since I last explored that subject. I will also rank her ten best videos. I know she has made more than ten music videos, but I will order the ten essential Kate Bush videos. Before getting to that, I am going to tackle all of her singles. I have counted thirty-eight singles. This is all of her singles and not just U.K. I have excluded the 2012 remix of Running Up That Hill (A Deal with God) and the 2022 reissue, as they are essentially similar or identical to the 1985 original. However, I am including the Little Shrew (Snowflake) single from last year, as it is a radio edit so is different to the 2011 version from 50 Words for Snow - and that was not released as a single. I am also not including Don’t Give Up as it is a Peter Gabriel single and not a Kate Bush one. For each, I have included the year they were released as singles and (where necessary) the albums they are from. I will spend time exploring the top ten, though I will simply rank the other twenty-eight. Like album and video rankings, people might disagree with where I place the singles! She never released a bad single, though it is clear some were weaker than others. Here are numbers thirty-eight to eleven:

38. Lyra (2007, The Golden Compass Soundtrack)

37. Deeper Understanding (2011, Director’s Cut)

36. Love and Anger (1990, The Sensual World)

35. And So Is Love (1994, The Red Shoes)

34. Ne t'enfuis pas (1983, standalone single)

33. The Dreaming (1982, The Dreaming)

32. There Goes a Tenner (1982, The Dreaming)

31. Rocket Man (I Think It's Going to Be a Long, Long Time) (1991, Two Rooms: Celebrating the Songs of Elton John & Bernie Taupin)

30. Hammer Horror (1978, Lionheart)

29. December Will Be Magic Again (1980, standalone single)

28. Experiment IV (1986, The Whole Story)

27. The Man I Love (ft. Larry Adler) (1994, The Glory of Gershwin)

26. Strange Phenomena (1979, The Kick Inside)

25. Wild Man (2011, 50 Words for Snow)

24. Symphony in Blue (1979, Lionheart)

23. King of the Mountain (2005, Aerial)

22. Moments of Pleasure (1993, The Red Shoes)

21. Eat the Music (1993, The Red Shoes)

20. Little Shrew (Snowflake) (2024, standalone single/radio edit)

19. Moving (The Kick Inside, 1978)

18. Rubberband Girl (1993, The Red Shoes)

17. Sat in Your Lap (1981, The Dreaming)

16. The Red Shoes (1994, The Red Shoes)

15. Wow (1979, Lionheart)

14. Breathing (1980, Never for Ever)

13. Army Dreamers (1980, Never for Ever)

12. Suspended in Gaffa (1982, The Dreaming)

11. Cloudbusting (1985, Hounds of Love)

TEN

This Woman’s Work (1989, The Sensual World)

“John Hughes, the American film director, had just made this film called ‘She’s Having A Baby’, and he had a scene in the film that he wanted a song to go with. And the film’s very light: it’s a lovely comedy. His films are very human, and it’s just about this young guy – falls in love with a girl, marries her. He’s still very much a kid. She gets pregnant, and it’s all still very light and child-like until she’s just about to have the baby and the nurse comes up to him and says it’s a in a breech position and they don’t know what the situation will be. So, while she’s in the operating room, he has so sit and wait in the waiting room and it’s a very powerful piece of film where he’s just sitting, thinking; and this is actually the moment in the film where he has to grow up. He has no choice. There he is, he’s not a kid any more; you can see he’s in a very grown-up situation. And he starts, in his head, going back to the times they were together. There are clips of film of them laughing together and doing up their flat and all this kind of thing. And it was such a powerful visual: it’s one of the quickest songs I’ve ever written. It was so easy to write. We had the piece of footage on video, so we plugged it up so that I could actually watch the monitor while I was sitting at the piano and I just wrote the song to these visuals. It was almost a matter of telling the story, and it was a lovely thing to do: I really enjoyed doing it” Roger Scott Interview, BBC Radio 1 (UK), 14 October 1989 - Kate Bush Encyclopedia

NINE

The Sensual World (1989, The Sensual World)

“Because I couldn’t get permission to use a piece of Joyce it gradually turned into the song about Molly Bloom the character stepping out of the book, into the real world and the impressions of sensuality. Rather than being in this two-dimensional world, she’s free, let loose to touch things, feel the ground under her feet, the sunsets, just how incredibly sensual a world it is. (…) In the original piece, it’s just ‘Yes’ – a very interesting way of leading you in. It pulls you into the piece by the continual acceptance of all these sensual things: ‘Ooh wonderful!’ I was thinking I’d never write anything as obviously sensual as the original piece, but when I had to rewrite the words, I was trapped. How could you recreate that mood without going into that level of sensuality? So there I was writing stuff that months before I’d said I’d never write. I have to think of it in terms of pastiche, and not that it’s me so much” Len Brown, ‘In The Realm Of The Senses’. NME (UK), 7 October 1989” - Kate Bush Encyclopedia

EIGHT

Night of the Swallow (1983, The Dreaming)

“Unfortunately a lot of men do begin to feel very trapped in their relationships and I think, in some situations, it is because the female is so scared, perhaps of her insecurity, that she needs to hang onto him completely. In this song she wants to control him and because he wants to do something that she doesn’t want him to she feels that he is going away. It’s almost on a parallel with the mother and son relationship where there is the same female feeling of not wanting the young child to move away from the nest. Of course, from the guys point of view, because she doesn’t want him to go, the urge to go is even stronger. For him, it’s not so much a job as a challenge; a chance to do something risky and exciting. But although that woman’s very much a stereotype I think she still exists today” Paul Simper, ‘Dreamtime Is Over’. Melody Maker (UK), 16 October 1982 - Kate Bush Encyclopedia

SEVEN

Them Heavy People (1978, The Kick Inside)

“The idea for ‘Heavy People’ came when I was just sitting one day in my parents’ house. I heard the phrase “Rolling the ball” in my head, and I thought that it would be a good way to start a song, so I ran in to the piano and played it and got the chords down. I then worked on it from there. It has lots of different people and ideas and things like that in it, and they came to me amazingly easily – it was a bit like ‘Oh England’, because in a way so much of it was what was happening at home at the time. My brother and my father were very much involved in talking about Gurdjieff and whirling Dervishes, and I was really getting into it, too. It was just like plucking out a bit of that and putting it into something that rhymed. And it happened so easily – in a way, too easily. I say that because normally it’s difficult to get it all to happen at once, but sometimes it does, and that can seem sort of wrong. Usually you have to work hard for things to happen, but it seems that the better you get at them the more likely you are to do something that is good without any effort. And because of that it’s always a surprise when something comes easily. I thought it was important not to be narrow-minded just because we talked about Gurdjieff. I knew that I didn’t mean his system was the only way, and that was why it was important to include whirling Dervishes and Jesus, because they are strong, too. Anyway, in the long run, although somebody might be into all of them, it’s really you that does it – they’re just the vehicle to get you there.

I always felt that ‘Heavy People’ should be a single, but I just had a feeling that it shouldn’t be a second single, although a lot of people wanted that. Maybe that’s why I had the feeling – because it was to happen a little later, and in fact I never really liked the album version much because it should be quite loose, you know: it’s a very human song. And I think, in fact, every time I do it, it gets even looser. I’ve danced and sung that song so many times now, but it’s still like a hymn to me when I sing it. I do sometimes get bored with the actual words I’m singing, but the meaning I put into them is still a comfort. It’s like a prayer, and it reminds me of direction. And it can’t help but help me when I’m singing those words. Subconsciously they must go in” Kate Bush Club newsletter number 3, November 1979 - Kate Bush Encyclopedia

SIX

Babooshka (1980, Never for Ever)

“Apparently it is grandmother, it’s also a headdress that people wear. But when I wrote the song it was just a name that literally came into my mind, I’ve presumed I’ve got it from a fairy story I’d read when I was a child. And after having written the song a series of incredible coincidences happened where I’d turned on the television and there was Donald Swan singing about Babooshka. So I thought, “Well, there’s got to be someone who’s actually called Babooshka.” So I was looking throughRadio Timesand there, another coincidence, there was an opera called Babooshka. Apparently she was the lady that the three kings went to see because the star stopped over her house and they thought “Jesus is in there”.’ So they went in and he wasn’t. And they wouldn’t let her come with them to find the baby and she spent the rest of her life looking for him and she never found him. And also a friend of mine had a cat called Babooshka. So these really extraordinary things that kept coming up when in fact it was just a name that came into my head at the time purely because it fitted” Peter Powell interview, Radio 1 (UK), 11 October 1980 - Kate Bush Encyclopedia

FIVE

The Big Sky (1986, Hounds of Love)

‘The Big Sky’ was a song that changed a lot between the first version of it on the demo and the end product on the master tapes. As I mentioned in the earlier magazine, the demos are the masters, in that we now work straight in the 24-track studio when I’m writing the songs; but the structure of this song changed quite a lot. I wanted to steam along, and with the help of musicians such as Alan Murphy on guitar and Youth on bass, we accomplished quite a rock-and-roll feel for the track. Although this song did undergo two different drafts and the aforementioned players changed their arrangements dramatically, this is unusual in the case of most of the songs” Kate Bush Club newsletter, Issue 18, 1985 - Kate Bush Encyclopedia

FOUR

The Man with the Child in His Eyes (1978, The Kick Inside)

“The inspiration for ‘The Man With the Child in His Eyes’ was really just a particular thing that happened when I went to the piano. The piano just started speaking to me. It was a theory that I had had for a while that I just observed in most of the men that I know: the fact that they just are little boys inside and how wonderful it is that they manage to retain this magic. I, myself, am attracted to older men, I guess, but I think that’s the same with every female. I think it’s a very natural, basic instinct that you look continually for your father for the rest of your life, as do men continually look for their mother in the women that they meet. I don’t think we’re all aware of it, but I think it is basically true. You look for that security that the opposite sex in your parenthood gave you as a child” Self Portrait, 1978 - Kate Bush Encyclopedia

THREE

Running Up That Hill (A Deal with God) (1985, Hounds of Love)

“It is very much about the power of love, and the strength that is created between two people when they’re very much in love, but the strength can also be threatening, violent, dangerous as well as gentle, soothing, loving. And it’s saying that if these two people could swap places – if the man could become the woman and the woman the man, that perhaps they could understand the feelings of that other person in a truer way, understanding them from that gender’s point of view, and that perhaps there are very subtle differences between the sexes that can cause problems in a relationship, especially when people really do care about each other” The Tony Myatt Interview, November 1985 - Kate Bush Encyclopedia

TWO

Hounds of Love (1985, Hounds of Love)

“[‘Hounds Of Love’] is really about someone who is afraid of being caught by the hounds that are chasing him. I wonder if everyone is perhaps ruled by fear, and afraid of getting into relationships on some level or another. They can involve pain, confusion and responsibilities, and I think a lot of people are particularly scared of responsibility. Maybe the being involved isn’t as horrific as your imagination can build it up to being – perhaps these baying hounds are really friendly” Kate Bush Club newsletter, 1985 - Kate Bush Encyclopedia

ONE

Wuthering Heights (1978, The Kick Inside)

“When I first read Wuthering Heights I thought the story was so strong. This young girl in an era when the female role was so inferior and she was coming out with this passionate, heavy stuff. Great subject matter for a song.

I loved writing it. It was a real challenge to precis the whole mood of a book into such a short piece of prose. Also when I was a child I was always called Cathy not Kate and I just found myself able to relate to her as a character. It’s so important to put yourself in the role of the person in a song. There’s no half measures. When I sing that song I am Cathy.

(Her face collapses back into smiles.) Gosh I sound so intense. Wuthering Heights is so important to me. It had to be the single. To me it was the only one. I had to fight off a few other people’s opinions but in the end they agreed with me. I was amazed at the response though, truly overwhelmed” (ate’s Fairy Tale, Record Mirror (UK), February 1978 - Kate Bush Encyclopedia

Before coming to the album ranking, I have selected the best ten Kate Bush videos. There is some tough competition. People might have their own opinions and change the order, but I am pretty happy with my top ten. Such a visionary when it came to videos, I especially love when Bush stepped behind the camera and directed. There are examples of her work below. Here are the ten best Kate Bush videos…

TEN: The Sensual World

Directors: Kate Bush/Peter Richardson

From the Album: The Sensual World (1989)

NINE: This Woman’s Work

Directors: Kate Bush/John Alexander

From the Album: The Sensual World (1989)

EIGHT: Experiment IV

Director: Kate Bush

From the Album: The Whole Story (1986)

SEVEN: Army Dreamers

Director: Keith (‘Keef’) MacMillan

From the Album: Never for Ever (1980)

SIX: Breathing

Director: Keith MacMillan

From the Album: Never for Ever (1980)

FIVE: Wuthering Heights

Director: Keith MacMillan

From the Album: The Kick Inside (1978)

FOUR: Running Up That Hill (A Deal with God)

Director: David Garfath

From the Album: Hounds of Love (1985)

THREE: Little Shrew (Snowflake)

Director: Kate Bush

From the Album: Standalone 2024 single release/radio edit

TWO: Cloudbusting

Director: Julian Doyle

From the Album: Hounds of Love (1985)

ONE: Hounds of Love

Director: Kate Bush

From the Album: Hounds of Love (1985)

I am going to end by ranking Kate Bush’s ten studio albums. In each case, I shall include the release date, producer(s), and a sample review. I will also include the album in full. There is tough competition again but, once more, some albums superior to others. There is of course personal bias, but there will be common ground: people agreeing with the ranking. If anyone had some other opinions then let me know. This is where I rank Kate Bush’s albums…

TEN: Director’s Cut

Release Date: 16th May, 2011

Producer: Kate Bush

Review:

“During her early career, Kate Bush released albums regularly despite her reputation as a perfectionist in the studio. Her first five were released within seven years. After The Hounds of Love in 1985, however, the breaks between got longer: The Sensual World appeared in 1989 and The Red Shoes in 1993. Then, nothing before Aerial, a double album issued in 2005. It's taken six more years to get The Director's Cut, an album whose material isn't new, though its presentation is. Four of this set's 11 tracks first appeared on The Sensual World, while the other seven come from The Red Shoes. Bush's reasons for re-recording these songs is a mystery. She does have her own world-class recording studio, and given the sounds here, she's kept up with technology. Some of these songs are merely tweaked, and pleasantly so, while others are radically altered. The two most glaring examples are "Flower of the Mountain" (previously known as "The Sensual World") and "This Woman's Work." The former intended to use Molly Bloom's soliloquy from James Joyce's novel Ulysses as its lyric; Bush was refused permission by his estate. That decision was eventually reversed; hence she re-recorded the originally intended lyrics. And while the arrangement is similar, there are added layers of synth and percussion. Her voice is absent the wails and hiccupy gasps of her youthful incarnation. These have been replaced by somewhat huskier, even more luxuriant and elegant tones. On the latter song, the arrangement of a full band and Michael Nyman's strings are replaced by a sparse, reverbed electric piano which pans between speakers. This skeletal arrangement frames Bush's more prominent vocal which has grown into these lyrics and inhabits them in full: their regrets, disappointments, and heartbreaks with real acceptance. She lets that voice rip on "Lilly," supported by a tougher, punchier bassline, skittering guitar efx, and a hypnotic drum loop. Bush's son Bertie makes an appearance as the voice of the computer (with Auto-Tune) on "Deeper Understanding." On "RubberBand Girl," Bush pays homage to the Rolling Stones' opening riff from "Street Fighting Man" in all its garagey glory (which one suspects was always there and has now been uncovered). The experience of The Director's Cut, encountering all this familiar material in its new dressing, is more than occasionally unsettling, but simultaneously, it is deeply engaging and satisfying” – AllMusic

NINE: The Sensual World

Release Date: 16th October, 1989

Producer: Kate Bush

Review:

“Even its most surreal songs are rooted in self-examination. “Heads We’re Dancing” seems like a dark joke—a young girl is charmed on to the dancefloor by a man she later learns is Adolf Hitler—but poses a troubling question: What does it say about you, if you couldn’t see through the devil’s disguise? Its discordant, skronky rhythms make it feel like a formal ball taking place in a fever dream, and Bush’s voice grows increasingly panicky as she realizes how badly she’s been duped. As far-fetched as its premise was, its inspiration lay close to home: A family friend had told Bush how shaken they’d been after they’d taken a shine to a dashing stranger at a dinner party, only to find out they’d been chatting to Robert Oppenheimer.

It’s more fanciful than most of The Sensual World’s little secrets. To hear someone recall formative childhood truths (the lush grandeur of “Reaching Out”) and lingering romantic pipedreams (the longing of “Never Be Mine”) is like being given a reel of their memory tapes and discovering what makes them tick. On “The Fog,” she’s paralyzed by fear until she remembers the childhood swimming lessons her father gave her, his voice cutting through the misty harps like an old ghost. Relationships on the album can be sticky and thorny. “Between a Man and a Woman” is half-dangerous and half-sultry, its snaking rhythms mirroring the round-in-circles squabbling of a couple. When a third party tries to interfere, they’re told to back off. This time, unlike on “Running Up That Hill (A Deal With God),” there’s no point wishing for a helping hand from God.

But if there are no miracles, there are at least songs that sound like them. For “Rocket’s Tail,” Bush enlisted the help of Trio Bulgarka, who she fell in love with after hearing them on a tape Paddy gave her. The three Bulgarian women didn’t speak English and had no idea what they were singing about, but it didn’t matter. They sound more like mystics during its a capella first half, and when it eventually blows up into a glammy stomper with Dave Gilmour’s electric guitar caterwauling like a Catherine wheel, their vocals still come out on top: cackling like gleeful witches, whooping like they’re watching sparks explode in the night sky. Its weird, wonderful magic offered a simple message: Life is short, so enjoy moments of pleasure before they fizzle out.

Perhaps that’s why there are glimmers of hope even in the album’s most desperate circumstances. “Deeper Understanding” is a bleak sci-fi tale about a lonely person who turns to their computer for comfort, and in doing so isolates themselves even more. But while there’s an icy chill to the verses, Trio Bulgarka imbue the computer’s voice with golden warmth. Bush wanted it to sound like the “visitation of angels,” and hearing the chorus is like being wrapped in a celestial hug. She pulls off a similar trick on “This Woman’s Work,” which she wrote for John Hughes’ film She’s Having a Baby, although her vivid, devastating interpretation of its script has taken on a far greater life of its own. It captures a moment of crisis: a man about to be walloped with the sledgehammer of parental responsibilities, frozen by terror as he waits for his pregnant wife outside the delivery room, his brain a messy spiral of regrets and guilty thoughts. Yet Bush softens the song’s building panic attack with soft musical touches so it rushes and swirls like a dream, even as reality becomes a waking nightmare. “It’s the point where has to grow up,” said Bush. “He’d been such a wally.”

She didn’t need to prove her own steeliness to anyone, especially the male journalists who patronized her and harped on her childishness as a way of cutting her down to size. Instead, The Sensual World is the sound of someone deciding for themselves what growing up and grown-up pop should be, without being beholden to anyone else’s tedious definitions. It gave her a new template for the next two decades, inspiring both the smooth, stylish art-rock of 1993’s The Red Shoes and the picturesque beauty of 2005’s Aerial. Like Molly Bloom, Bush had set herself free into a world that wasn’t mundane, but alive with new, fertile possibility” – Pitchfork

EIGHT: The Red Shoes

Release Date: 1st November, 1993

Producer: Kate Bush

Review:

“It's not all fainting hearts on Shoes, though. The mood ranges from the pure pop of "Rubberband Girl" to the exuberant reel of the title cut (an homage to the classic film), from the wistful verse and funky chorus of the Prince collaboration "Why Should I Love You?" to the West Indies-flavored "Eat the Music." The Red Shoes is a solid collection of well-crafted and seductively melodic showcases for Bush's hypercabaret style.

Canadian Jane Siberry has often been compared to Bush, partly due to the convenience of lumping together quirky female singer/songwriters but also as an acknowledgment that both are working in a personal subgenre of art rock. And there are similarities between Siberry's When I Was a Boy and Shoes – both display a preoccupation with the difficulty of separating pain and love; both evoke a questioning spirituality and a distinctly feminine earthiness.

But Siberry's album is as funereal and expansive as Bush's is tight and energized. Nothing Siberry has done in the past quite prepares the listener for this album's prevalent mood of spooky obsession, bewilderment and resignation, and deathbed reflections. Though there's occasionally a rumble in the reverie ("All the Candles in the World," for instance, is positively funky), the overall ambience is prayerful, abetted by a production that often creates a cathedral of silence between the low tones (husky viola or cello filigrees) and the spare front line (an acoustic piano or guitar). Though songs like "Temple" (co-produced by Siberry and Brian Eno) and "Candles" are immediately likable, long free-floating meditations like "Sweet Incarnadine" and "The Vigil (The Sea)" are the album's centerpieces, gradually unfolding songs about love and dying.

It would all be horribly pretentious – if not maudlin – in the hands of a lesser talent, but Siberry approaches her task with a fearless simplicity, resisting easy irony or cleverness. Like Bush she creates dramatic structure by using a variety of voices, from brimming-heart full tones to deadpan whispers. When I Was a Boy is a difficult disc to get into – the languidness at its center can be off-putting – but a little patience rewards you with a gem. (RS 670)” – Rolling Stone

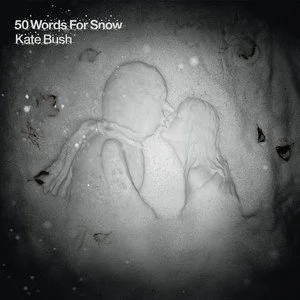

SEVEN: 50 Words for Snow

Release Date: 21st November, 2011

Producer: Kate Bush

Review:

“But in one sense, these peculiarities aren't really that peculiar, given that this is an album by Bush. She has form in releasing Christmas records, thanks to 1980's December Will Be Magic Again, on which she imagined herself falling softly from the sky on a winter's evening. She does it again here on opener Snowflake, although anyone looking for evidence of her artistic development might note that 30 years ago she employed her bug-eyed Heeeath-CLIFF! voice and plonking lyrical references to Bing Crosby and "old St Nicholas up the chimney" to conjure the requisite sense of wonder. Today, she gets there far more successfully using only a gently insistent piano figure, soft flurries of strings and percussion and the voice of her son Bertie.

Meanwhile, Fry's is merely the latest unlikely guest appearance – Bush has previously employed Lenny Henry, Rolf Harris (twice) and the late animal imitator Percy Edwards, the latter to make sheep noises on the title track of 1982's The Dreaming. Equally, Fairweather Low is not the first person called upon to pretend to be someone else on a Bush album, although she usually takes that upon herself, doing impersonations to prove the point: Elvis on Aerial's King of the Mountain, a gorblimey bank robber on There Goes a Tenner. Finally, in song at least, Bush has always displayed a remarkably omnivorous sexual appetite: long before the Yeti and old Snow Balls showed up, her lustful gaze had variously fixed on Adolf Hitler, a baby and Harry Houdini.

No, the really peculiar thing is that 50 Words for Snow is the second album in little over six months from a woman who took six years to make its predecessor and 12 to make the one before that. If it's perhaps stretching it to say you can tell it's been made quickly – no one is ever going to call an album that features Lake Tahoe's operatic duet between a tenor and a counter-tenor a rough-and-ready lo-fi experience – it certainly feels more intuitive than, say, Aerial, on which a lot of time and effort had clearly been expended in the pursuit of effortlessness. For all the subtle beauty of the orchestrations, there's an organic, live feel, the sense of musicians huddled together in a room, not something that's happened on a Bush album before.

That aside, 50 Words for Snow is extraordinary business as usual for Bush, meaning it's packed with the kind of ideas you can't imagine anyone else in rock having. Taking notions that look entirely daft on paper and rendering them into astonishing music is very much Bush's signature move. There's something utterly inscrutable and unknowable about how she does it that has nothing to do with her famous aversion to publicity. Better not to worry, to just listen to an album that, like the weather it celebrates, gets under your skin and into your bones” – The Guardian

SIX: The Dreaming

Release Date: 13th September, 1982

Producer: Kate Bush

Review:

“An embarrassment of riches then, bestowed upon an unworthy rabble. The Dreaming was released to a baffled public but the more open-minded sectors of the music press acknowledged Bush’s achievement. Despite many laudatory notices, watching Bush and Gabriel’s respective appearances on Old Grey Whistle Test confirms what she was up against. Gabriel is afforded due reverence as an art-rock renaissance man, Bush, on the other hand, while covering roughly the same ground, is ever so slightly mocked. Behind her unwavering propriety, irritation smoulders. As with her appearance on Pebble Mill, the usually sympathetic Paul Gambaccini constantly frames the music in context of its radio playability or lack thereof. Bush looks bewildered and more than a little wan. The music she had created was no longer so easily assimilated by daytime TV.

Another tour was talked about but never transpired. She left London. At her parents East Wickham home she created a 48 track studio and returned three years later with the masterpiece Hounds Of Love, knocking Madonna’s Like A Virgin off the top spot. It elevated her into the pantheon of greats, a grand dame of Brit-pop at the tender age of 27. The first side with its consistent rhythms, arresting hooks and l’amour fou turned her into a hi-tech post hippy hit machine. The singles’ videos were glossy excursions, some of them conceived on film rather than video. By the ‘Hounds Of Love’ promo she was directing herself. Another area the "shyest megalomaniac" wrestled control of. ‘The Ninth Wave’ was another tribute to her imaginative powers, the song suite being the sexy, acceptable face of prog rock. She even had a hit in America. Although she had to change the name from ‘A Deal With God’ to ‘Running Up That Hill’.

But it was The Dreaming that lay the groundwork. It ignited US critical interest in her (including the hard-assed Robert Christgau and the burgeoning college radio scene finally gave Bush an outlet there. Hounds Of Love, remains the acme of this singular talent’s achievements. It uses ethnic instrumentation while sounding nothing like the world music that would be popularized through the 80s. It is a record largely constructed with cutting edge technology that eschews the showroom dummy bleeps associated with synth-pop. At the time, she talked of using technology to apply "the future to nostalgia", an interesting reverse of Bowie’s nostalgic Berlin soundtrack for a future that never came. Like Low, The Dreaming is Bush’s own "new music night and day" a brave volte face from a mainstream artist. It remains a startlingly modern record too, the organic hybridization, the use of digital and analogue techniques, its use of modern wizadry to access atavistic states (oddly, Rob Young’s fine portrait of the singer in Electric Eden only mentions this album in passing).

For such an extreme album, its influence has been far-reaching. ABC, then in their Lexicon Of Love prime, named it as one of their favourites, as did Bjork whose similar use of electronics to convey the pantheistic seems directly descended from The Dreaming. Even The Cure’s Disintegration duplicates the track arrangement on the sleeve and the request that ‘this album was mixed to be played loud’. ‘Leave It Open’‘s vari-speed vocals even prefigure the art-damaged munchkins of The Knife vocal arsenal. Field Music/The Week That Was arrayed themselves with sonics that seem heavily indebted to Bush’s work here. Graphic novelist Neil Gaiman even had a character sing lyrics from the title track in his The Sandman series. John Balance of post-industrialists Coil confessed that the album’s songs were all ideas that he later tried to write. But Bush got there first. And The Dreaming remains a testament to the exhilarating joy of "letting the weirdness in” – The Quietus

FIVE: Lionheart

Release Date: 10th November, 1978

Producer: Andrew Powell (assisted by Kate Bush)

Review:

“Proving that the English admired Kate Bush's work, 1978's Lionheart album managed to reach the number six spot in her homeland while failing to make a substantial impact in North America. The single "Hammer Horror" went to number 44 on the U.K. singles chart, but the remaining tracks from the album spin, leap, and pirouette with Bush's vocal dramatics, most of them dissipating into a mist rather than hovering around long enough to be memorable. Her fairytale essence wraps itself around tracks like "In Search of Peter Pan," "Kashka From Baghdad," and "Oh England My Lionheart," but unravels before any substance can be heard. "Wow" does the best job at expressing her voice as it waves and flutters through the chorus, with a melody that shimmers in a peculiar but compatible manner. Some of the tracks, such as "Coffee Homeground" or "In the Warm Room," bask in their own subtle obscurity, a trait that Bush improved upon later in her career but couldn't secure on this album. Lionheart acts as a gauge more than a complete album, as Bush is trying to see how many different ways she can sound vocally colorful, even enigmatic, rather than focus on her material's content and fluidity. Hearing Lionheart after listening to Never for Ever or The Dreaming album, it's apparent how quickly Bush had progressed both vocally and in her writing in such a short time” – AllMusic

FOUR: Aerial

Release Date: 7th November, 2005

Producer: Kate Bush

Review:

“As might be expected of an album which breaks a 12-year silence during which she began to raise a family, there's a core of contented domesticity to Kate Bush's Aerial. It's not just a case of parental bliss - although her affection for "lovely, lovely Bertie" spills over from the courtly song specifically about him, to wash all over the second of this double-album's discs, a song-cycle about creation, art, the natural world and the cycling passage of time.

It's there too in the childhood reminiscence of "A Coral Room", the almost autistic satisfaction of the obsessive-compulsive mathematician fascinated by "Pi" (which affords the opportunity to hear Bush slowly sing vast chunks of the number in question, several dozen digits long - which rather puts singing the telephone directory into the shade), and particularly "Mrs Bartolozzi", a wife, or maybe widow, seeking solace for her absent mate in the dance of their clothes in the washing machine. "I watched them going round and round/ My blouse wrapping itself round your trousers," she observes, slipping into the infantile - "Slooshy sloshy, slooshy sloshy, get that dirty shirty clean" - and alighting periodically upon the zen stillness of the murmured chorus, "washing machine".

The second disc takes us through a relaxing day's stroll in the sunshine, from the sequenced birdsong of the "Prelude", through a pavement artist's attempt to "find the song of the oil and the brush" through serendipity and skill ("That bit there, it was an accident/ But he's so pleased/ It's the best mistake he could make/ And it's my favourite piece"), through the gentle flamenco chamber-jazz "Sunset" and the Laura Veirs-style epiphanic night-time swim in "Nocturn", to her dawn duet with the waking birds that concludes the album with mesmeric waves of synthesiser perked up by brisk banjo runs.

There's a hypnotic undertow running throughout the album, from the gentle reggae lilt of the single "King of the Mountain" and the organ pulses of "Pi" to the minimalist waves of piano and synth in "Prologue". Though oddly, for all its consistency of mood and tone, Aerial is possibly Bush's most musically diverse album, with individual tracks involving, alongside the usual rock-band line-up, such curiosities as bowed viol and spinet, jazz bass, castanets, rhythmic cooing pigeons, and her bizarre attempt to achieve communion with the natural world by aping the dawn chorus. Despite the muttered commentary of Rolf Harris as The Painter, it's a marvellous, complex work which restores Kate Bush to the artistic stature she last possessed around the time of Hounds of Love” – The Independent

THREE: Never for Ever

Release Date: 8th September, 1980

Producers: Kate Bush/Jon Kelly

Review:

“In that sense, the LP’s final two tracks, despite being the most explicitly political Bush had ever written, aren’t quite the radical outliers they seemed back in 1980. For all their polemical grist, she saw them as personal, poignant stories just like all her others, and although most critics lauded them for reckoning with ‘real life’ in a way her older efforts didn’t, their power transcends such bogus rules of authenticity. They’re spectacular not because their subject matter is inherently weightier than yarns about paranoid Russian wives or grumpy syphilitic composers, but because Bush brings it to life with exactly the same kind of exquisite, singular imagination; they’re political songs that have been twisted and transmogrified so they can exist in her strange universe, not the other way round. If Never For Ever made her a bolder, sharper songwriter, it was still absolutely on her own terms.

And so on ‘Army Dreamers’, a misty waltz about a mother racked with grief and guilt when her son is killed on military manoeuvres, Bush resembles an otherworldly prophet rather than a common-or-garden tub-thumper. “Wave a bunch of purple flowers/ To decorate a mammy’s hero,” she sings softly, sadly, bitterly, her gentle Irish lilt mingling with its sweet, woozy mandolin and the Fairlight’s unnerving samples of cocking rifles (Bush thought the accent, combined with the thwack of bodhrán, had a poetic vulnerability her regular voice lacked – not the last time she’d invoke her Celtic roots for emotional heft). Its gauzy prettiness gives it the air of a nightmare taking place inside a snow globe, twice as crushing for her delicate touch.

Nothing, though, is as devastating as the closing ‘Breathing’, a vision of nuclear doomsday with a horrifying wrinkle, like Threads turned into a poisonous lullaby (Bush, ever prescient, actually beat the film by three years). She sings as a terrified foetus breathing in toxic fumes inside the womb, slowly being killed by the blast’s fallout because mother doesn’t stand for comfort at all in this grim new world. Every element is beautifully brutal: the brooding electronics that fill the air like dangerous smog; the chilling, fairytale-gone-wrong image of plutonium chips “twinkling in every lung”, made extra-disturbing by gorgeous, glimmering chimes; the ominous scientific lecture that builds to a billowing, mushroom-cloud explosion of ungodly noise, followed by the background singers’ dread chant of “We are all going to die!” Most harrowing of all is the strangled, throat-tearing terror in Bush’s voice. In the past she’d shrieked, yelled, whooped and wailed, but she’d never all-out screamed like she screams here, a guttural cry for help that freezes the blood: “Leave me something to breathe!” Bush was as proud of its apocalyptic nightmare as she’d been unmoved by Lionheart. “It’s my little symphony,” she boasted to ZigZag.

Like ‘Wuthering Heights’, Never For Ever made history: the first No 1 album by a British female solo artist. Yet its significance transcends chart milestones. For the next decade Bush would build on its potential to become, as she joked to Q in 1989, the “shyest megalomaniac you’re ever likely to meet”. Whereas her first three albums were squeezed into two-and-a-half years, the subsequent three spanned nine. The next one, the bewildering, avant-garde masterpiece The Dreaming, was the first she produced entirely by herself; soon after, she built a studio-come-sanctuary near her family home and hunkered away to make the flawless Hounds Of Love. Each record introduced new inspirations, new instruments, new collaborators and new methods, all indebted to Never For Ever’s triumph of bloody-minded determination. It doesn’t belong in her imperial period, but that imperial period wouldn’t exist without it.

Whenever people told Bush they didn’t understand Never For Ever’s title, she patiently explained it encapsulated her belief that all things, good and bad, eventually passed. “We are all transient,” she declared in her fan newsletter, and it’s hard to think of a finer choice for an album that, even now, exists in a glorious state of flux. Never For Ever proved how great Bush could be when given the control and freedom she craved. More tantalisingly still, it promised the best was yet to come” – The Quietus

TWO: Hounds of Love

Release Date: 16th September, 1985

Producer: Kate Bush

Review:

“On Hounds of Love, the singer who started directing her own videos at this point becomes total auteur, and takes such a firm grasp on every aspect of the recording process that she often replaces Del Palmer, her own lover, on bass. On “Mother Stands for Comfort,” an all-knowing maternal contrast to the delusional papa of “Cloudbusting,” she duets with German jazz bassist Eberhard Weber, who plays yielding mother to Bush’s wayward daughter. Her Fairlight clatters with the crash of broken dishes while her piano gently wanders, but Weber’s fretless bass maintains its compassion, even when Bush lets loose some freaky primal-scream scatting toward the end.

Skies, clouds, hills, trees, lakes—along with everything else, Hounds of Love is also a heated paean to nature. On the cover, Bush reclines between two canines with a knowing familiarity that almost suggests cross-species congress. She honors the sensual world's benign blessings on “The Big Sky” even while Youth’s raucous bass suggests earthquakes. Bush references its elements with childlike awe: “That cloud looks like Ireland,” she squeals. “You’re here in my head like the sun coming out,” she sighs in “Cloudbusting,” and her stormy emotions are reflected by the music’s turbulence. But nature’s destruction can also inspire us to seek solace in spirituality, and that’s what happens on Side Two’s singular suite, “The Ninth Wave.”

Bush plays a sailor who finds herself shipwrecked and alone. She slips into a hypothermia-induced limbo between wakefulness and sleep (“And Dream of Sheep”), where nightmares, memories and visions distort her consciousness to the point where she cannot distinguish between reality and illusion. Is she skating, or trapped “Under Ice”? During her hallucinations, she sees herself in a prior life as a necromancer on trial; instead of freezing, she visualizes herself burning (“Waking the Witch”). Her spirit leaves her body and visits her beloved (“Watching You Without Me”). Then her future self confronts her present being and begs her to stay alive (“Jig of Life”). A rescue team reaches her just as her life force drifts heavenward (“Hello Earth”), but in the concluding track, “The Morning Fog,” flesh and spirit reunite, and she vows to tell her family how much she loves them.

As her sailor drifts in and out of consciousness, Bush floats between abstract composition and precise songcraft. Her character’s nebulous condition gives her melodies permission to unmoor from pop’s constrictions; her verses don’t necessarily return to catchy choruses, not until the relative normality of “The Morning Fog,” one of her sweetest songs. Instead, she’s free to exploit her Fairlight’s capacity for musique concrete. Spoken voices, Gregorian chant, Irish jigs, oceanic waves of digitized droning, and the culminating twittering of birds all collide in Bush’s synth-folk symphony. Like most of her lyrics, “The Ninth Wave” isn’t autobiographical, although its sink-or-swim scenario can be read as an extended metaphor for Hounds of Love’s protracted creation: Will she rise to deliver the masterstroke that guaranteed artistic autonomy for the rest of her long career and enabled her to live a happy home life with zero participation in the outside world for years on end, or will she drown under the weight of her colossal ambition?

By the time I became one of the few American journalists to have interviewed her in person in 1985, Bush had clinched her victory. She’d flown to New York to plug Hounds of Love, engaging in the kind of promotion she’d rarely do again. Because she thoroughly rejected the pop treadmill, the media had already begun to marginalize her as a space case, and have since painted her as a tragic, reclusive figure. Yet despite her mystical persona, she was disarmingly down-to-earth: That hammy public Kate was clearly this soft-spoken individual’s invention; an ever-changing role she played like Bowie in an era when even icons like Stevie Nicks and Donna Summer had a Lindsey Buckingham or a Giorgio Moroder calling many of the shots.

It was a response, perhaps, to the age-old quandary of commanding respect as a woman in an overwhelmingly masculine field. Bush's navigation of this minefield was as natural as it was ingenious: She became the most musically serious and yet outwardly whimsical star of her time. She held onto her bucolic childhood and sustained her family’s support, feeding the wonder that’s never left her. Her subsequent records couldn’t surpass Hounds of Love’s perfect marriage of technique and exploration, but never has she made a false one. She’s like the glissando of “Hello Earth” that rises up and plummets down almost simultaneously: Bush retained the strength to ride fame’s waves because she’s always known exactly what she was—simply, and quite complicatedly, herself” – Pitchfork

ONE: The Kick Inside

Release Date: 17th February, 1978

Producer: Andrew Powell

Review:

“The tale's been oft-told, but bears repeating: Discovered by a mutual friend of the Bush family as well as Pink Floyd's David Gilmour, Bush was signed on Gilmour's advice to EMI at 16. Given a large advance and three years, The Kick Inside was her extraordinary debut. To this day (unless you count the less palatable warblings of Tori Amos) nothing sounds like it.

Using mainly session musicians, The Kick Inside was the result of a record company actually allowing a young talent to blossom. Some of these songs were written when she was 13! Helmed by Gilmour's friend, Andrew Powell, it's a lush blend of piano grandiosity, vaguely uncomfortable reggae and intricate, intelligent, wonderful songs. All delivered in a voice that had no precedents. Even so, EMI wanted the dullest, most conventional track, James And The Cold Gun as the lead single, but Kate was no push over. At 19 she knew that the startling whoops and Bronte-influenced narrative of Wuthering Heights would be her make or break moment. Luckily she was allowed her head.

Of course not only did Wuthering Heights give her the first self-written number one by a female artist in the UK, (a stereotype-busting fact of huge proportions, sadly undermined by EMI's subsequent decision to market Bush as lycra-clad cheesecake), but it represented a level of articulacy, or at least literacy, that was unknown to the charts up until then. In fact, the whole album reads like a the product of a young, liberally-educated mind, trying to cram as much esoterica in as possible. Them Heavy People, the album's second hit may be a bouncy, reggae-lite confection, but it still manages to mention new age philosopher and teacher G I Gurdjieff. In interviews she was already dropping names like Kafka and Joyce, while she peppered her act with dance moves taught by Linsdsay Kemp. Showaddywaddy, this was not.

And this isn't to mention the sexual content. Ignoring the album's title itself, we have the full on expression of erotic joy in Feel It and L'Amour Looks Something Like You. Only in France had 19-year olds got away with this kind of stuff. A true child of the 60s vanguard in feminism, Strange Phenomena even concerns menstruation: Another first. Of course such density was decidedly English and middle class. Only the mushy, orchestral Man With The Child In His Eyes, was to make a mark in the US, but like all true artists, you always felt that Bush didn't really care about the commercial rewards. She was soon to abandon touring completely and steer her own fabulous course into rock history” – BBC